Borderline melancholy

Misha Maslennikov

Interview with Mikhail Skuridin,

one of the founders of the Kolodozero community at the Church

of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary in the village of Kolodozero.

The text of the interview was published in 'M-Journal', January 2013

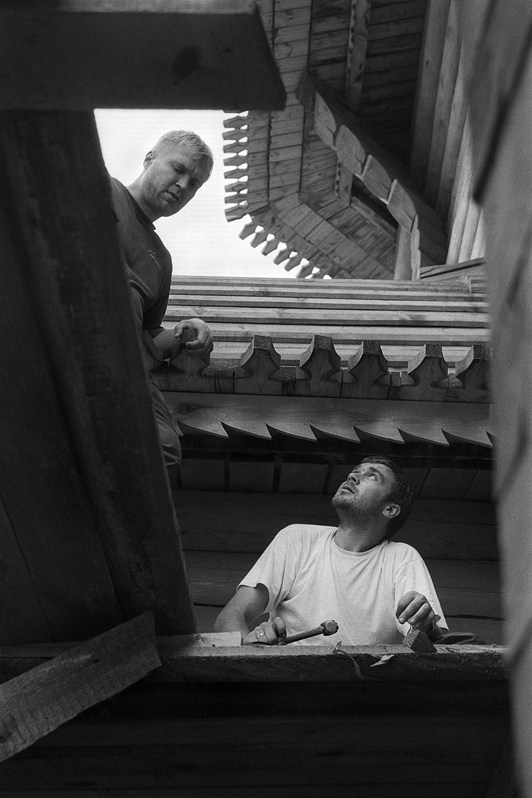

Headman of Kolodozero community Mikhail Skuridin in sawdust after work on construction of wooden church

Pogost village, Pudozh district, Karelia, Russia. 2007

Mishka Skuridin died in a car accident. It happened in winter, on an icy highway, on the way from Moscow to Karelia. Having left his parents' house in the Moscow region, he was hurrying to his new home in Kolodozersky Pogost. The new car skidded at speed and crashed under the wheels of an oncoming MAZ. The wounded Volchok, Mishka’s shepherd dog, got out of the mangled car and crawled into the forest to die. Mishka loved his young dog very much, as he did all his previous dogs with equally strange and tragic fates. This love of his was always filled with deep emotions and an unprecedented care for his pets. Marriage was also in his immediate plans. He was preparing the ground for starting a family in the North, where from the very beginning he built and beautified a church, where he was a choirmaster, a singer, and a psalm-reader all rolled into one. A wonderful musician, a virtuoso carpenter, a student of the psychology department of Moscow State University, he carried the burden of being the head of the newly formed community in a businesslike manner. Not every capital city resident, with all the desire and enthusiasm, manages to get used to life in the northern latitudes. Mishka, with unfailing cordiality, year after year, received numerous guests in his home. And when I managed to get out to Kolodozero, I listened with genuine interest to his stories about life in the northern hinterland. Mishka had finally become related to the North, and this unity was the most sincere and humane.

Anomie of society, as the destruction of the basic elements

of culture, contributes to two types of flight:

external migration and internal migration.

Flight to another country is the same for everyone,

but 'flight within oneself' is different for everyone.

Liberty.SU

Difficulties, they are often quite natural, they do not contradict either the joy of life or its meaning. It seems to me that difficulties are not so much external in nature, there is a very strong connection with God, I just do not have the ability to use this connection. So, for example, in Moscow, I seem to know myself as a fairly conscientious employee, responsible and all that… Well… Yes, when you are your own head, it turns out to be more difficult. You need to fully formulate the task for yourself, define goals, make a work schedule, plans, start doing all this — this is a little harder. And if you do not do this, then, sometimes, you 'fall into', especially in winter. Winter, it is dark, quiet and cold here. No unnecessary noise, no outside information. You see, this is what the city has in abundance, that is why winter is not really felt in the city. There is always an opportunity to hanging your brain with something. A large amount of information, such cultural, if necessary, but here it is different. Here, if you haven’t got ready in advance…

Last winter, I just didn’t get ready. It just happened. I can’t say that I did nothing all winter. I did something. As usual, around the house, around the church, but it was somehow very disorganized, mazily, and overall left the feeling that winter was a period of inaction. It always tries to be like that. Stiffness in movements and an oppressive feeling of emptiness. It seems to me that it’s like that in the North. It’s one thing to live for a couple of weeks or a month. To escape from Moscow. It’s wonderful. I remember, I arrived. It wasn’t even winter, it was still October. It was autumn in full swing. Exactly what I needed at that moment. When there’s nowhere to escape from it, it becomes very tense. Nothing fills your head, nothing unnecessary. Here it was discovered that if something of your own was missing, in advance, all with your own thoughts, not even Moscow ones, already transformed… But I still moved here. And then, in ninety-nine, there were no such plans. There was an opportunity to live in a remote village. Tambichozero is the first place in Karelia that caught my eye after long wanderings around Russia. Only one person lived there. I lived with him for about a month. That was the beginning.

Headman Mikhail Skuridin with guest from Moscow

Pogost village, Pudozh district, Karelia, Russia. 2007

I had two full winters in Kolodozero, from the fifth to the sixth and from the sixth to the seventh zero years. At some point, I really wanted to run away from here, because I had the feeling that there was no life here and there could not be. Everything in Moscow remained. And something really did remain. Like, temptation. You know, such characteristic little things accumulate, maybe they exist in other places, maybe they even exist in Moscow, you just don’t notice them there. It’s hard for me to explain what exactly is happening. Let’s take relationships, say, with people… You understand that a person is standing there, telling you something, and it seems interesting, and some topic for conversation has come up… Then suddenly — bam, and everything turns out so that this topic is touched upon quite abstractly, that in fact… The person just needs something from you.

Here with local people, maybe because there is no such 'white noise', it becomes much more obvious. Maybe it was like that before, I didn’t pay attention… Something simple and unpretentious is needed. For example, money. And it’s not about its presence or absence (they may be there!), it just becomes unpleasant. And what were we standing here and talking for? Or like in work relations, how they developed. They were building a temple. Of course, there was a need for workers (now there is no need). And this was also very striking. I could not understand the motivation, let’s say…

— I am not satisfied with your salary.

— I am not satisfied with the way you talk to me.

— You do not respect me.

I would understand that, but there are no such motivations. And what are there?

— I just don’t want to.

— I don’t want to anymore!

And you explain to the person that he has talent, that he is a great carpenter by definition. Maybe he hasn’t done this before, he doesn’t have experience yet, but it is obvious. I’m talking about a specific case that got me the most. A young guy who had just returned from the army, a local. It was so easy for me that I didn’t have to stand over him and check how he worked, or explain to him until the last stage how to do this or that. Because I only outlined the task in general terms, not yet imagining how to solve it, but I was already sure that he would figure it out and do it himself.

And he did. He was naturally good at it. In the end, he became a real master. After working for us for about eight months, he came to me and said: 'I’m leaving.' I said: 'What happened? Not enough money? We’ll do more.' — 'No, — he said, — it’s fine. The money is fine, I’m leaving anyway.' I said: 'What? What’s wrong? Well, let’s talk, we’ll figure it out…' — 'No, no, there are no hard feelings at all.' — 'Did you find yourself another job? ' — 'No, I didn’t find anything. What can you find here? ' I say: 'So what? Well, look, we have rich prospects here. There are no carpenters as such in the area. Well, there are some, but there are few of them, the area is huge.' — 'Screw it!…'

Headman in reflection after a day’s work rests on the povet of community house

Pogost village, Pudozhsky district, Karelia, Russia. 2007

Here. This short and indifferent 'screw it', abstract, hanging in the air. You understand: this is it! It killed me with its absurdity. I realized that this is some kind of boundless swamp spreading out before you, a swamp of someone else’s consciousness. 'Screw it'… I even began to catch some things in myself, well, not like that, but I was surprised at myself. Well, why? Is it really so hard to force yourself to go and do this or that work? No, my own 'screw it' did not arise, but at some point it becomes very difficult. Rather, a thought appeared like: 'What’s the point? Why? ' Well, maybe this is the same 'screw it', just in different words? This is a big psychological problem.

A football match among local boys and visitors to the community

Pogost village, Pudozhsky district, Karelia, Russia. 2007

What other difficulties? We really haven’t frozen here even once, because we live in normal houses and plan to stock up on firewood. Even if they were damp, you can still heat the house. It’s fine for the men. We didn’t go hungry, it seems like nothing even came close. If you go out and, say, you don’t have running water or steam heating at home, you have to light the stove in the morning, carry water (To do this, first cut a hole that was frozen ten centimeters during the night), then it’s not really that hard. It’s just the specifics of everyday life, and it’s perceived normally, it’s not depressing. Do you know what winter in the North is? It’s… It’s something borderline melancholy. What kind of Moscow is that? The soul is exposed, and you look at these white-white hopeless days and the same white-white hopeless nights.

Priest Father Arkady and headman Mikhail Skuridin on the choir before the Liturgy

Pogost village, Pudozhsky district, Karelia, Russia. 2009

And this melancholy has a metaphysical character, it is even needed somewhere and, it seems, useful. It tests a person. Exactly. You leave the house in the morning — and there is not a sound. During the day there are some sounds, rare. The day is very short, there is very little light, the morning is dark, the second half of the day is also dark, such a long, long darkness. And all around it all stands and is silent. Ice, field, forest… Here it all stands and is silent. And it is all so huge, and here is this little house on the edge, and I am standing next to it… And then there is nothing at all. This is powerful. And, in fact, this is wonderful, because in theory I should like it. But at that moment, when you don’t know what you are actually supposed to do here, it can simply drive you crazy.

Bathing day. Several buckets of water from the lake ice-hole

Pogost village, Pudozhsky district, Karelia, Russia. 2009

There is nowhere to run from here. This whole huge space, completely silent, frozen, simply demands that you do something. You understand, otherwise your consciousness… It will simply slide away and it will not exist. And you are standing on the edge of this endless space, behind you is also the door to the house, here is a village, and on the other side is a road, another village, the city of Kargopol, the city of Pudozh… There is no point in explaining. Consciousness no longer perceives this. Consciousness probably knows, but it is silent. Deaf. There really is nothing there at all. It is absolutely the same there: endless snow, cold and silence. It is terribly beautiful, and this beauty knocks you down. In small doses it is exceptionally pleasant, and in those that are no longer under your control, when it is always with you (and will last not sure how long until spring!), you understand that this is — wow. Something needs to be done about it.

Two women returning home after Christmas night service

Pogost village, Pudozhsky district, Karelia, Russia. 2009

I think this is one of the sources of alcoholism. There was one case. In the fall, about two years ago. Fall, like winter, can be a not very happy time if it rains all the time. I went to Pudozh on some business. And there I am. All the business is already done, the time is two o’clock in the afternoon, the bus will arrive only in two hours, I can’t leave for the village earlier. I am standing at the bus station, it is drizzling, and, you know, everything is so gray-gray-gray. Absolutely gray everything: houses, people, cars, roads. In general. That is, it was such a hopeless day, incredibly dull.

Bus stop on a snowy road, Ust-reka village

Pogost village, Pudozhsky district, Karelia, Russia. 2009

And there is nothing to do. So I went on my way. I buy a bottle of beer, stand there and drink. I finish the bottle of beer, look around, and everything has already blossomed with colors. Unexpectedly. That’s when this thought struck me: so that’s why people drink here. They just can’t stand it anymore. And Pudozh, compared to the village, is an even more nightmarish place. It is not a civilized city, that is, it is small, it cannot be considered as Moscow or Petrozavodsk. And it is no longer a village, where the joys of village life are also not in sight.

Dog named Volchok on the path between the temple and the dwelling

Pogost village, Pudozhsky district, Karelia, Russia. 2009

That makes the situation even sadder. I’m standing at the bus stop and I understand that right now, in theory, I want to go and buy another bottle of beer, so that it shines even brighter or lasts longer. I think, and so you can not stop after that. And easily felt that you can not stop. And spend my psychological talents on getting money from some other person. In Pudozh, this is very well developed. I waited for the bus, returned to Kolodozero, home, wood burner… That is, we sat, had dinner. That’s what cheered me up. And tomorrow we went to work, to the temple.

Conversation recorded by Misha Maslennikov

January 2009