Marc Riboud

Vietnam 1966-1976

Carola Allemandi

Conversation with Guglielmo Pellerino at the exhibition 'Marc Riboud. Vietnam 1966-1976'

at the Guimet Museum, Paris

Text published in 'Snaporaz', May 2025

In Paris, at the Guimet Museum, the exhibition “Marc Riboud. Vietnam 1966-1976‘ has been set up at the Guimet Museum in Paris, curated by Lorène Durret, Zoé Barthélémy and the Association of Friends of Marc Riboud. It is dedicated to the renowned French photojournalist who was a member of the Magnum Agency and the author of the famous photograph Jeune fille à la fleur (’Girl with a Flower”), which became a symbol of the peace movements of 1968. The exhibition, which runs until 12 May, features a selection of photographs from Marc Riboud’s numerous reports on Vietnam during and immediately after the conflict. This year (in fact, in just two days' time) marks the 50th anniversary of the end of the war.

Often, to appreciate the shots of great photojournalists, it is not enough to know the history of photography or have an eye trained to read images in depth: you need someone to complete the story from a historical perspective, thus providing the appropriate tools to understand the context in which those photographs were taken.

To get a better look at Marc Riboud’s photographs of Vietnam, I met with Guglielmo Pellerino, a historian and researcher specialising in Antonio Gramsci and Ho Chi Minh (with a particular focus on French colonialism in Vietnam). In addition to his research activities, he edits texts for the National Edition of Antonio Gramsci’s Writings. In 2022, he wrote the introduction to the first Italian publication of Ho Chi Minh’s The Process of French Colonisation, published by MarxVentuno and edited by Alessia Franco.

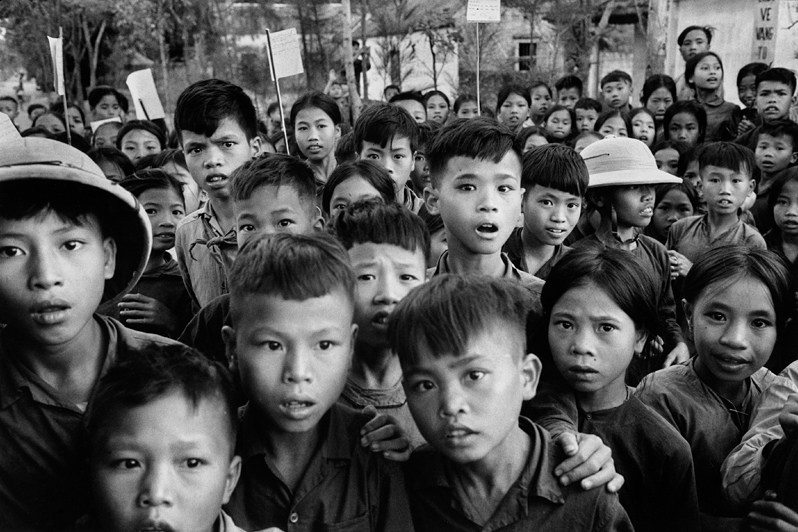

Announcement of the end of Operation Rolling Thunder in Phat Diem

North Vietnam. 1968

This image was taken in 1968 by Marc Riboud on the occasion of the announcement of the end of Operation Rolling Thunder in Phat Diem, as reported in the caption. What is meant by 'Operation Rolling Thunder'?

'Operation Rolling Thunder' refers to a massive aerial bombing campaign conducted by the United States against the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam), which began in March 1965 and ended, with some interruptions, in November 1968. This military operation had three main objectives: to stop the infiltration of troops and supplies from the North to the South, to discourage North Vietnam from continuing the war, and to strengthen the political stability and confidence of the government of the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam). It was a crucial moment in the history of this conflict: after years of bombing that had caused over 30,000 deaths among Vietnamese civilians, US public opinion — until then strongly influenced by a formidable propaganda machine set up by the government — was becoming increasingly opposed to the war. The costs of the operation had been enormous, and even today this military intervention can be considered one of the greatest strategic failures of the US army. In general, it can be said that the dissent generated by the US intervention would explode internationally, contributing to the birth of the 1968 movement shortly thereafter. Riboud’s photograph, taken in the days following the conclusion of that brutal operation, thus takes on symbolic value: it shows the end of a devastating, unprecedented military event and all the drama of a civilian population exhausted by years of bombing.

Hué On the main street of the citadel

South Vietnam, 1968

In this case, Marc Riboud manages to capture an almost impressionistic scene, the movement of the inhabitants of Hué with the buildings destroyed by the clashes in the background, which they seem to ignore. In the introduction you wrote for the Italian translation of Ho Chi Minh’s The Process of French Colonisation, published by MarxVentuno (2022), I was struck by the dichotomy you raise between the Vietnamese people’s ability to absorb the positive qualities of the cultures they came into contact with or were dominated by, and their necessary and tenacious resistance to colonial oppression. Perhaps this image can also be read in this sense: the dual plane that populates the horizon of the Vietnamese people, that of destruction and that of life, which manages to remain firmly anchored to its own identity and cultural heritage. What do you think?

It could be said that the history of Vietnam is, in fact, a long succession of attempts at domination that have been rejected and fought against with force: from China to France, from Japan to the United States. The history of the Vietnamese people is a history of resistance.

You lived in Vietnam for a few months in 2019, and you also visited Hué. What would a photograph taken on the same street look like today?

It is a photo that transcends time: I believe that this image could be exactly the same today, except for the buildings that have been demolished. Although Vietnam entered a new phase in its history in 1986 — the year of the Doi Moi policy, the opening up to the market — and is experiencing a strong wave of tourism, it seems to me that, at times, life has remained unchanged, even in the landscapes. Even time (this is the impression I got) seems to have retained different rhythms: beyond the chaos of cities like Hanoi, life seems to follow a slower pace than what we have learned to live with in the West. In colour and with intact buildings, it could be exactly the same photo: a normal scene of everyday life in Vietnam.

In this shot, we see a woman with two children in an emergency room in a school in Hué after the Tet Offensive. Photography has the advantage of being able to capture certain testimonies, but it must come to terms with the fact that it cannot see and convey everything. These three subjects thus become, in a way, emblematic of a broader phenomenon, which saw many other people forced to take refuge after the conflict. Can you tell us something about the Tet Offensive?

The Tet Offensive was certainly the most strategically significant operation carried out by the resistance and military forces of North Vietnam: it was a large-scale, widespread offensive launched during the Vietnamese New Year. It was a surprise attack that deeply affected the US army.

The Girl with the Flower, Protest against the Vietnam War

Washington, United States. 1967

Looking at this photograph, perhaps one of the most iconic in the history not only of photography but also specifically of the pacifist movements that were emerging at the time in support of the Vietnam War, I would like to ask you, as a historian, how useful you think this type of iconic image is in spreading a certain political awareness, and what limitations you see in their mass use.

I remember a line from Elio Petri’s 1979 film Dirty Hands (based on Jean-Paul Sartre’s play of the same name): “You can’t make a revolution with flowers”. When we talk about the US war of aggression in Vietnam, we can identify at least two images that have become iconic: the first is the photograph of the summary execution of a civilian accused of being part of the resistance army by a South Vietnamese officer. The photo dates back to 1 February 1968, during the Tet Offensive. This photograph was taken by Eddie Adams, who won the Pulitzer Prize thanks to that image. The second image, equally iconic, is that of Kim Phúc, the nine-year-old girl immortalised in that famous sequence of images depicting her, against her will, fleeing naked from a napalm bombing that had hit her village, her back completely burned. The photograph, taken on 8 June 1972 by Nick Út, also won the Pulitzer Prize.

The Vietnam War was the first “televised” war, reported day by day. It was a war that entered people’s homes through television. An impressive propaganda machine was built around the narrative of the US mission, with the aim of legitimising intervention in that region of the world. The operation was part of the policy of containment, i.e. the attempt to halt the spread of communism. However, those images of war, broadcast daily on television screens around the world, began to awaken consciences: suddenly, the war seemed less distant. When images of bombings and massacres began to circulate, even in the United States people began to doubt the legitimacy of that war. The images coming out of Vietnam inflamed the world and contributed to the birth of international solidarity movements: the victory of the Vietnamese people owes part of its success to that protest movement that put pressure on Western governments, to those millions of people around the world who took to the streets to demand an end to the invasion, people who went to jail rather than be complicit in the massacre. Demonstrations were held all over the world in support of the Vietnamese people, waving their flag and chanting the name of Ho Chi Minh, who had already led the struggle for liberation from French colonialism. Those protests are probably one of the greatest demonstrations of human solidarity in the last century. The iconic photos still exist today, of course. Perhaps, I would say, in an age when we are constantly exposed to images, it is more difficult to be captivated by a single image and make it a cause for commitment. The ability to arouse such emotions has been weakened, to say the least, but this also has to do with the hyper-individualistic society in which we live. This constant exposure to images, even the most atrocious ones, has numbed us somewhat. In any case, even if on a smaller scale, the images of the bombing of Gaza have undoubtedly helped to bring millions of people back onto the streets around the world. In any case, even if on a smaller scale, the images of the bombings in Gaza have undoubtedly helped to bring millions of people back onto the streets around the world. A widespread protest movement has also begun within universities, just as happened in the 1960s and 1970s around the Vietnam issue.

Of course, revolution cannot be achieved with flowers alone, or at least not exclusively. But every struggle, every form of resistance, requires all the energy possible, including creativity. Images have a strong communicative potential, as we well know. Sharing images is useful for raising awareness of a reality or an idea. But we cannot limit ourselves to this: we must transform reality, and theory must be translated into practice, as Marx said. In Vietnam, resistance had to be military, as it was a country invaded by foreign forces. In the West, it was necessary to generate active and radical protest to support the Vietnamese people. However, let us not forget that those who took to the streets in those years, even if they protested peacefully, still put their bodies in front of weapons and squads of people whose task was to repress dissent, even violently. The recent years of mobilisation for Gaza, to return to this example, which I think is relevant, have also taken place thanks to the sharing of images and counter-information. The fact that a numerically larger and more widespread movement has not developed is probably a reflection of today’s media system, which I would describe as toxic. Fortunately, counter-information has played its part. In any case, it is undeniable that there are similarities between what happened in Vietnam and what is happening in Palestine: the link with current events is there and is clear in the minds of those who study history, but it is also clear to those who are fighting and those who, in one way or another, are trying to keep attention focused on what is happening in Palestine. In May last year, while I was talking about colonialism and wars in Vietnam at the Polytechnic University of Turin, there was a student camp in support of the Palestinian people, where I found a banner that read: “From Vietnam to Palestine we will fight from one generation to the next”. It struck me deeply. Clearly, that war and the mobilisation it created left something in history and can still be an example.

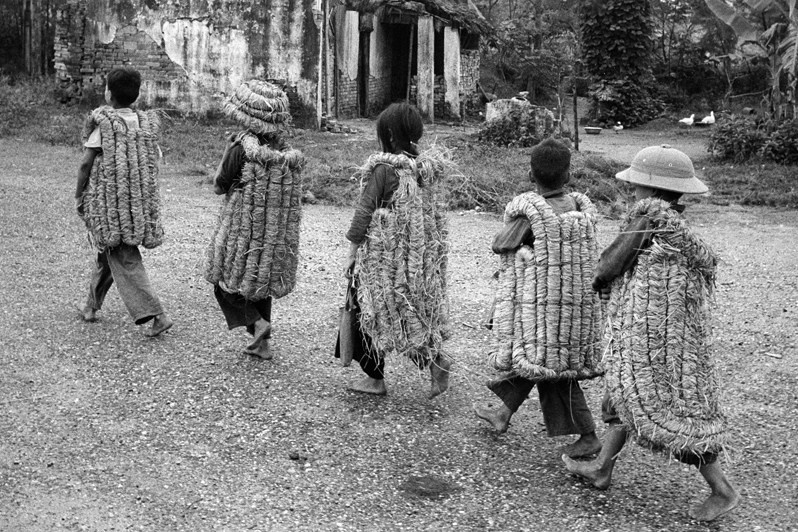

Leaving school in a coastal village

North Vietnam. 1969

In the images taken in Vietnam by Marc Riboud, one detail caught my eye: the substantial difference in the subjects' attitudes when faced with the camera. While the adults seem almost oblivious to the photographer, almost always looking elsewhere, the children seem transfixed by his presence. I would like you to tell us about the childhood you experienced in Vietnam, 50 years after this shot was taken.

When I was in Vietnam, I taught Italian at the university, so I interacted with young students, but they were still adults. However, as an observer, I can say that I had the impression that, in some way, a certain childishness had been preserved even among adults. I lived mainly in Hanoi, a city in close contact with the rest of the world, like all capitals, so my perception may be a little limited. However, it seemed to me that childhood was lighter and that adults themselves retained some of that lightness: for example, in the city of Hanoi, around Hoan Kiem Lake, at the weekend the area became a pedestrian zone where people gathered to dance in groups, sing, play music and play traditional games, almost as if it were a big village festival, with the difference that this took place in the largest city in Vietnam, which has a population of around 9 million. The simplicity of the games played by children and adults, the joy of sharing moments of fun with the community, seem to me to be a very different way of conceiving existence compared to the society in which we live. I believe that a cohesive society is also built on sharing moments of socialising of this kind. This struck me.

Incidentally, if these children in the photograph are around ten years old, it is possible that you may have met some of them, now in their sixties. What has happened in Vietnam over the last fifty years?

The final phase of the Vietnam War ended on 30 April 1975, the day of the last act of the offensive known as the “Ho Chi Minh Campaign”, named in honour of the Vietnamese leader who died in 1969. This offensive ended with the liberation of Saigon (later renamed Ho Chi Minh City) and then with the reunification of the country. Since the Doi Moi, which I mentioned earlier, the economy has changed: for years, Vietnam, although still considered a developing country, has been experiencing a phase of great economic growth, and tourism has intensified. Of course, every action that can have a beneficial effect in some respects also has negative consequences: for example, some natural sites are collapsing due to mass tourism; economic growth has also had an impact on the quality of work and the rights of workers, and pollution is another major problem, which can be seen in cities such as Hanoi. Like the rest of the world, Vietnam has also had to deal with the pandemic emergency, but despite its proximity to China, it has been a model of health crisis management in this regard. While elections were postponed in Italy, the National Congress of the Communist Party of Vietnam was held in Hanoi, bringing thousands of delegates to the capital. The management of the emergency was an interesting case and was praised, albeit cautiously, by the international press.

Children on their way to school, wearing thick straw vests to protect themselves from landmines

North

Vietnam. 1969

This image also contains a singular ambivalence: the heavy straw protection against anti-personnel mine shrapnel and the bare feet of the children. What do you see in this image? We often see the Vietnamese people walking barefoot. What can you tell us about this?

In this image, I see the essence of the Vietnamese resistance struggle: what we see is not one army fighting another army; it is an idea fighting against violence, oppression, colonialism, and imperialism. The struggle was always unequal, and this image is an example of that. But, thanks in part to Ho Chi Minh, the struggle of the Vietnamese people is still a symbol of struggle for all oppressed peoples.

Conversation recorded by Carola Allemandi

May 2025