Yamal: Non-Soviet Photo

Part 1

Alexander Shchemliaev

AND THE NORTH IS A DELICATE MATTER

The settlement of Yartsangi, conscientiously put on the map of the Tyumen region, turned out to be in reality a ‘residential massif’ of eight chums, picturesquely located on the bank of the Ob River. Of course, the name of streets and the numbering of houses are absent there …

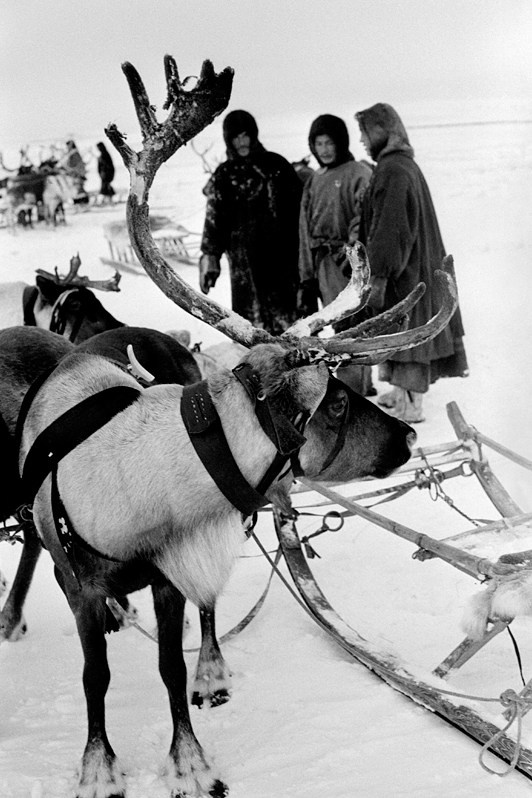

The reindeer herders of the 2nd Brigade call it their ancestral village. Old people, children and vacationers — people on holiday — live in this village, which is probably why there is an atmosphere of calm benevolence and pleasant idleness: I was often asked what was being done across the stream on the other side of the settlement, although it was enough to open the chums canopy to see it ...

The day after my arrival in Yartsangi, while walking along the river, I heard the sound of a helicopter coming in for a landing. The opportunity to film an interesting situation and maybe go for a ride drove me to the site of the event. After running the final part of the distance through the bushes, I jumped out into the open and almost collided with a helicopter pilot, who was carrying a huge bag of fresh fish to the helicopter in a pair with a local resident. The sight of a camera-wielding man suddenly appearing out of nowhere frightened the ‘ace of small aviation’ and he threw his end of the bag: of course he did, because he had been caught doing something wrong — a left flight to ‘support pants’. The final confusion in the pilot's soul was brought by his local business partner’, proudly announcing: ‘And this is our guest — a Moscow correspondent’. Only after much exhortation and assurances of loyalty did the pilot regain the power of speech to the extent necessary to say ‘yes’ to my request to fly with him to the herd.

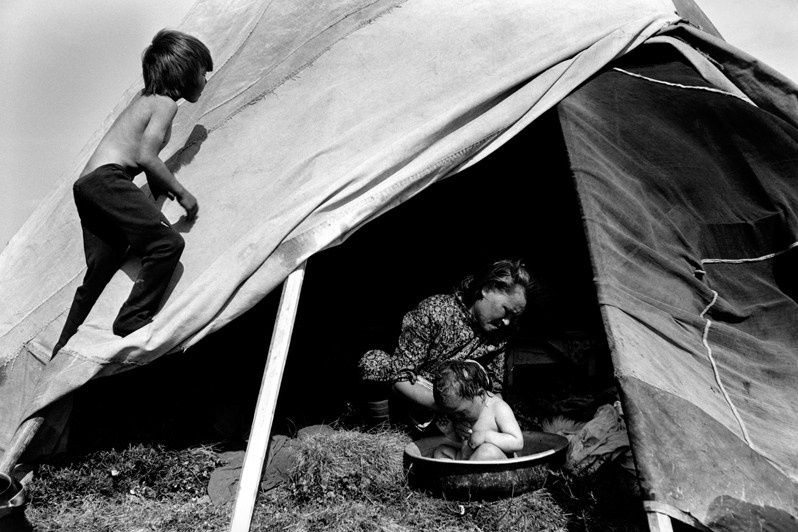

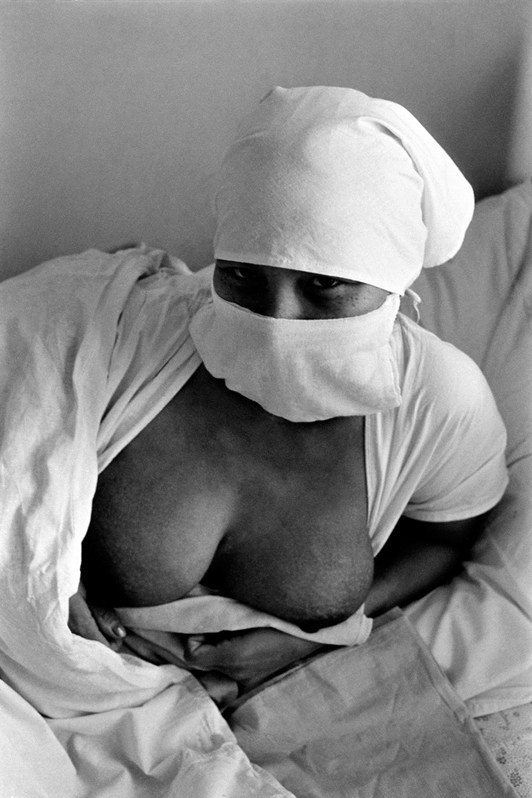

We landed near Brigade 1's car park, which was in a marshy area. It seemed that I found myself in another civilisation. People dressed in animal skins (malitsy) on one style of grey colour, island-topped plagues, dull tundra, and as for evil ‘there was a big mosquito’. The helicopter on which we arrived belonged to the sanitary aviation and made a special flight. Outwardly everything looked decent: the medics were dressed in white coats and behaved culturally, but the medical examination procedure was so fast that I did not have time to film it. In general, in Moscow doctors also do not treat patients with excessive attention and care, but here the process was going at record speed. People in white coats entered the tent, stepped over the dogs, asking on the way: ‘Will it bite?’, looked into the children's mouths, put packages of pills in the hands of women, politely greeted the men and went outside — that's it, this family had already joined the ‘free medical service’. Symbolically, ten days after this examination, an 11-year-old girl died in the brigade and was buried there in the tundra. I am not going to judge anyone, God forbid, the medics know the local conditions better, they have a hard job, they live there, after all, but I feel sorry for their patients.

I must admit that this day was very hard — in fact, my first contact with the real life of small indigenous peoples of the North was not as rosy as I had expected. During my journalistic trips I had to see enough and capture on film: the birth of a child, the death of people in hot spots, corpses and ruins after the earthquake in Armenia — a lot of grief and tragedy, but at the car park of the 1st reindeer herding brigade I was seized by a feeling of despondency and hopelessness of local life.

Fighting off the mosquitoes, I was the first to pile into the helicopter, muttering: ‘Fly to hell, we had no deal!’ Although, as far as the contract was concerned, there was no contract. There was no contract with any editorial office or organisation, but only naked enthusiasm, a desire to understand the mysterious local life and tell about it in photographs. It was all the more shameful that the first day I spent in the reindeer herding brigade made me sad. This is what ignorance of local conditions and romantic delusions about ‘living in harmony with nature’ lead to. I remembered that I learnt the location of the Yamal peninsula, as well as the origin of the name of the city of Khanty-Mansiysk from the names of two nations — Khanty and Mansi, in my fourth decade... My sad reflections were interrupted by a pilot's question: ‘Will you fly with us in the 2nd Brigade?’.

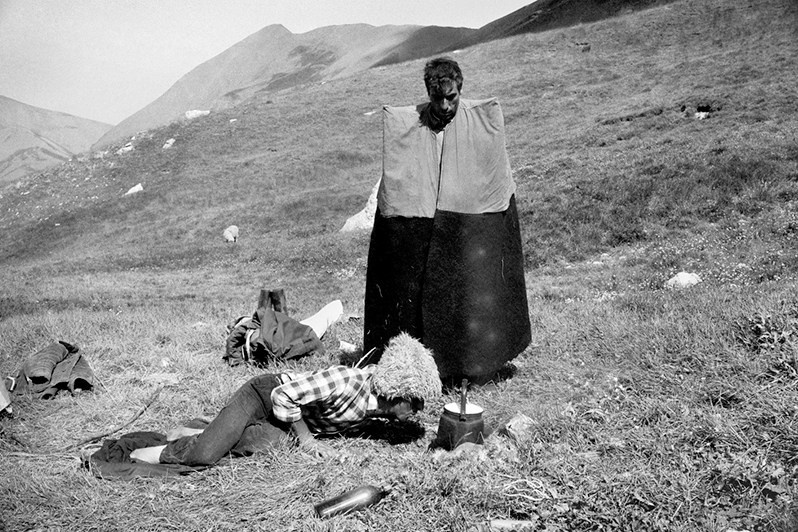

The camp of the second reindeer herding brigade, Kutopyugan (‘middle of the river’ in Nenets), was in the forest tundra. The nature here is more merciful, and there are fewer mosquitoes, so people walk in European clothes, which is more familiar to the urban man's eye.

As I approached the pilot, I said: ‘I think I'll stay here.’ To which I received a reply: ‘Go ahead!’

Then everything went on in turmoil: medics were loading on board, people waved to the departing helicopter (I, like everyone else, also waved), then people dispersed to chums, leaving me sitting alone on my rucksack. In the nearest chum they were talking in an unfamiliar language, children were cautiously looking at me from behind the canopy, dogs came up, sniffed my backpack and went on with their business. The situation was ridiculous: in a hurry nobody introduced me to anyone, and the locals did not understand who had come and why. For example, imagine a reindeer herder sitting in the stairwell of your town house, and you look through the door peephole and wonder what he is doing here.

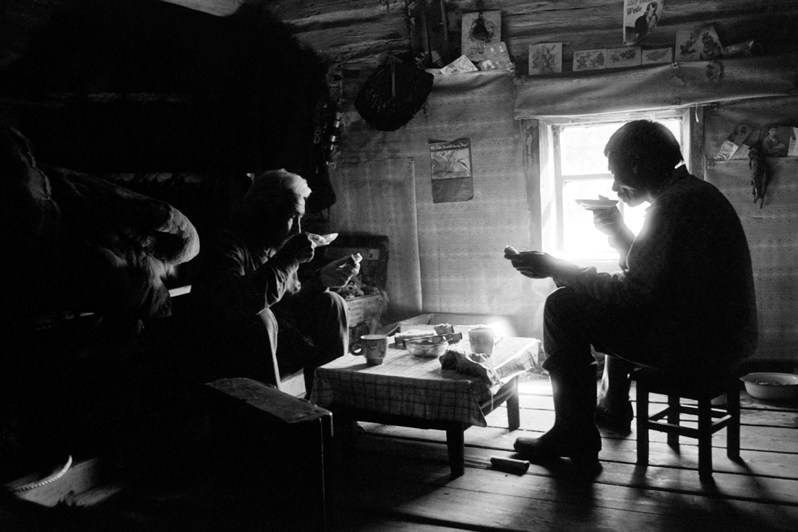

Fortunately, the people in the tundra are understanding and hospitable: having assessed the situation, I was invited to stay with a large family from a nearby chum, for which I bowed to them and wished them good health.

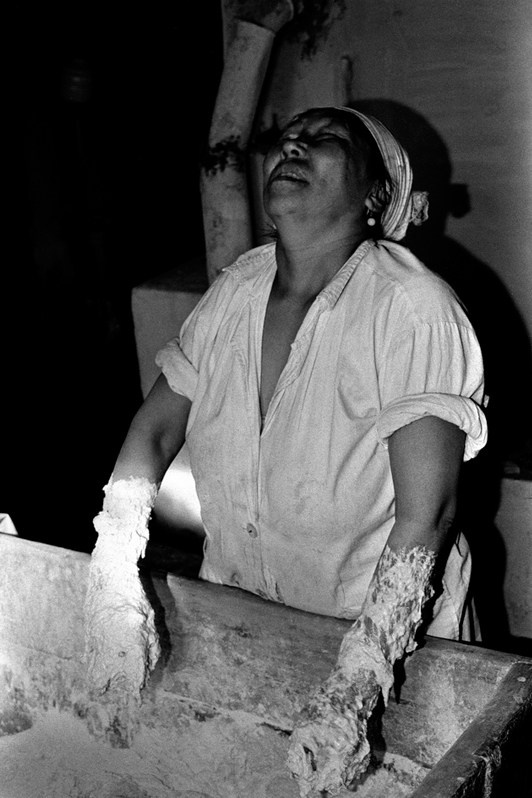

Apart from my host — a two-metre tall bulky man, a caring hostess, about whom we will talk below, three of their sons and two daughters, the dogs shared the night with me, tied up in different corners, which did not prevent them from having noisy nocturnal battles and loud quarrels. In such cases the dogs are first separated by loud shouting, then they try to put them to sleep by throwing swamp boots at them, and if these means do not help — they are taken out into the fresh air to the great joy of mosquitoes.

For a pampered Muscovite waking up from the noise of the refrigerator in the kitchen, the most terrible of the measures to stop dog fights was the shout of a reindeer herder, whose power, by virtue of industrial necessity, drowns out the stomping of a herd of two or three thousand reindeer.

Ignorance of foreign customs and living conditions is fraught with many misunderstandings for a traveller, and sometimes can lead to trouble: the proverb ‘the East is a delicate matter’ is true for all parts of the world, including the North.

One day I went into the far part of the plague, causing displeasure to the owners. The children secretly explained to me that by crossing an imaginary line through the hearth in the middle of the dwelling, a stranger could bring disease on the owner's head. In this ‘forbidden zone’ they keep a chest where good spirits who protect the family live, like the lares of the ancient Romans.

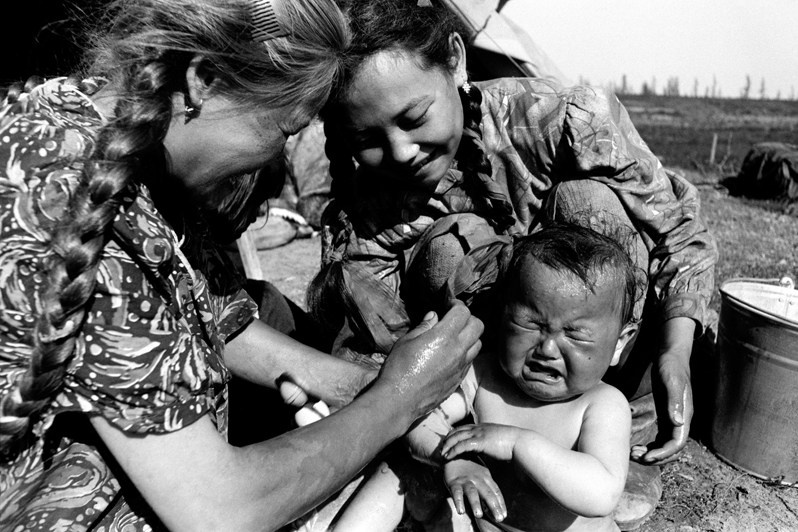

When the owner's one-year-old daughter fell ill, he opened the cherished chest and asked for help from his masters, the spirits listened and helped — the child, at least, recovered.

Another time I found straw in my summer kisas (short boots made of reindeer skins), given to me by kind-hearted Nenets to replace my wet shoes, and found nothing better than to throw it into the fire. My observation of the picturesque glare of the flames on the canopy of the plague was interrupted by a woman's scream (a thing quite atypical according to local customs). The hostess rushed to the hearth, snatched bundles of straw and trampled the fire with her feet. Having performed all these actions, she shouted in Nenets something incomprehensible to me, but, to all appearances, unflattering. The Russian-speaking men who entered the tent explained: the straw is used for drying shoes (a process necessary in the damp tundra), and it is stocked in autumn, and now it is only the middle of summer. ‘There is only one problem with this Russian’.

My relations with the owner of the chum were constantly complicated by two factors: firstly, she did not know Russian, just as I did not know Nenets, and secondly, her nature was too delicate and painfully sensitive. This woman cared about how I ate, how I walked, how I photographed her children, and she expressed her concerns to me, without giving me a moment's rest, through gestures, facial expressions, or through interpreters, if they were nearby.

Shortly before departure, I was filming a kaslanie - the transition of the brigade to a new car park. It was midday, it was hot, there was a ‘big mosquito’, which was joined by a gnat out of solidarity or just in season. They are different in size and bite differently, but the ‘pleasure’ from their bites is similar. In such conditions, even to go to the smallest necessity is either a difficult task or a painful process. After crossing the stream, I camouflaged myself in the bushes so as not to frighten the deer, which, although they are called domestic, are in fact, at best, semi-wild and, accordingly, fearful. The Argish (a column of sleds) started moving. Neither reindeer nor reindeer herders saw me, and the photo shooting was going on normally. Here is my mistress overcoming a difficult part of the way, and I froze in excitement: will she or won't she pass? No, the reindeer rushed to the side, afraid of water, the sledge hit a stump, and argish stopped. The situation is complicated: it is easier for the reindeer to move by inertia than to move the heavy sledges from the place after stopping. Because of this the formation breaks down, the reindeer herders get nervous, but the most unpleasant thing is that the animals, exhausted by the heat, lie down to rest in the frozen tundra, and it is a difficult task to get them up afterwards. The woman, having jumped down on the ground, began to actively remove the sledge from the stump, I enthusiastically photographed this fight from the bushes, as I would film a sports competition, and then my hostess shouted: ‘Lutsa (Russian), help me lift the sledge, you rotten stump!’ I realised quickly enough that the expression ‘stumpy stump’ referred not to me but to the obstacle, but I still cannot understand: how did this woman see me in the bushes and, most importantly, when did she learn Russian?

Alexander Shchemliaev 1992

SEVERIANE Magazine No. 3, 2012