Yamal: Non-Soviet Photo

Part 2

Alexander Shchemliaev

SHAMAN’S GIFT

In the village of Tazovsky, Yamalo-Nenets District, the locals took the news that I was going to see the shaman calmly: here they knew almost nothing about him, but in the tundra, among reindeer herders, the reaction was quite different. ‘Lutsa (Russian), don’t be afraid of him, he won’t hurt you, even though he is a black shaman, not a white one, don’t be afraid of him anyway; you don’t have reindeer’, — that’s how Marik, the brigadier’s wife, reassured me …

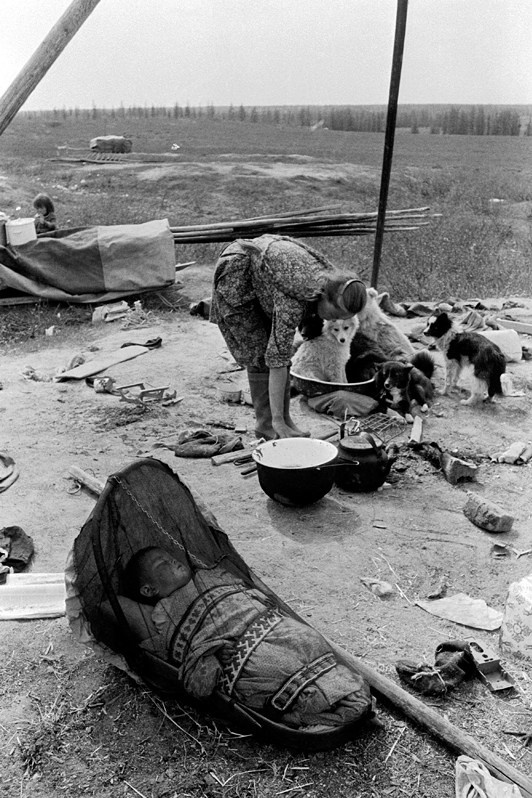

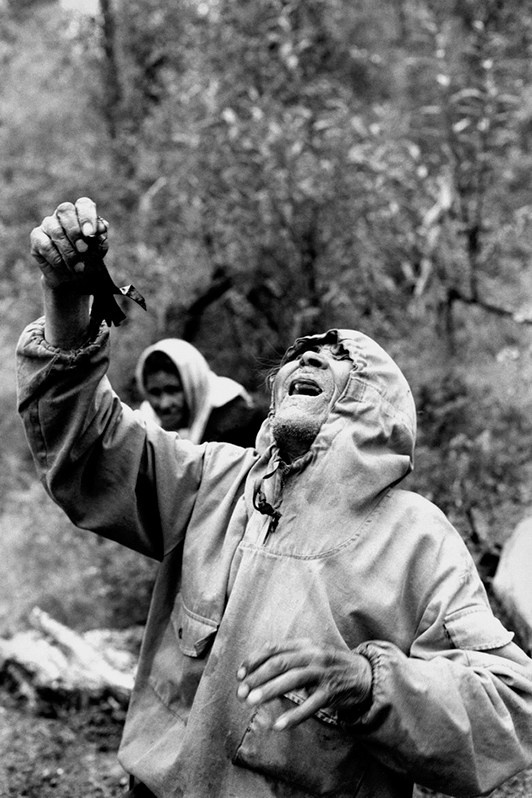

There was a terrible heat, which drove not only the inhabitants of the tent, but also the dogs, which had lost all militancy. The whole family was assembled: the foreman and his youngest son were weaving a tanzyan (lasso), the eldest son of conscription age was lounging under the canopy waiting for the night watch. While waiting out the heat, husband and wife, interrupting each other, told me about the shaman. ‘He is not afraid of anyone in the tundra: he comes uninvited into any tent he likes. If he does not nagudit, can let spoil or do so, like him oleni, himself escapes to his chum. They remembered, as in the child their straight in the range of plague, but also there to him dosnosilya kriki. And in the morning they heard them recalling how the shaman had cut his chest with a knife, and the blood was gushing, and how white birds flew away from the fire upwards, where the smoke from the tent went.

The parents' story was only occasionally interrupted by the eldest son's chuckle from beneath the canopy. As for the younger son, he listened with his mouth open, holding an unfinished tenjian by the ends. His face expressed fear, but for some reason I was the one who was most afraid. I felt like a policeman who was gathering a dossier on a dangerous criminal whom I would have to fight in the future. Though I am Russian, but I was born in the Far East in the Nanai village of Verkhnyaya Ekon, on the Amur River, and since my childhood, somewhere deep in my consciousness, it turns out, lived this hidden, primal fear, which, until now, I did not even realise. And to confess, during the foreman's story, I couldn't help it: I believed every word he said, because in my childhood we avoided meeting the old Nanai man who was said to be a shaman.

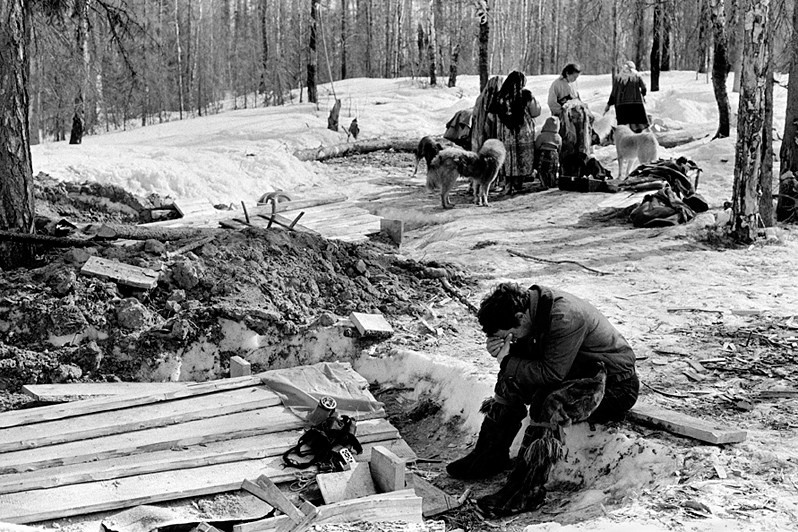

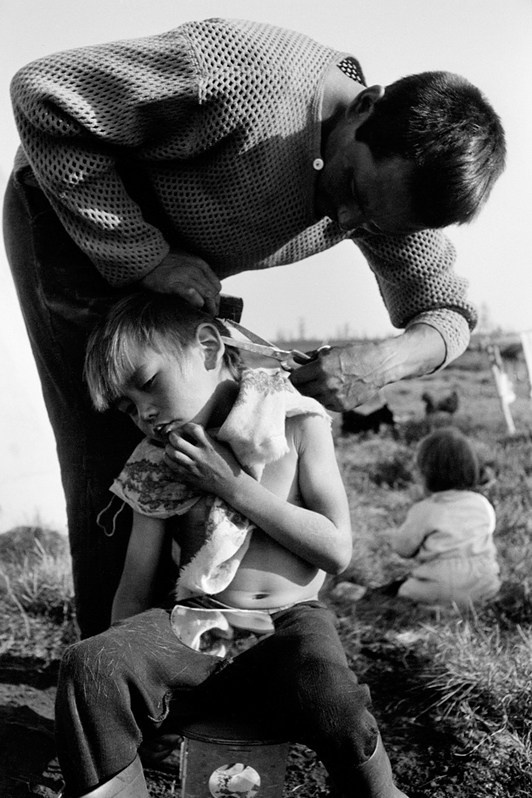

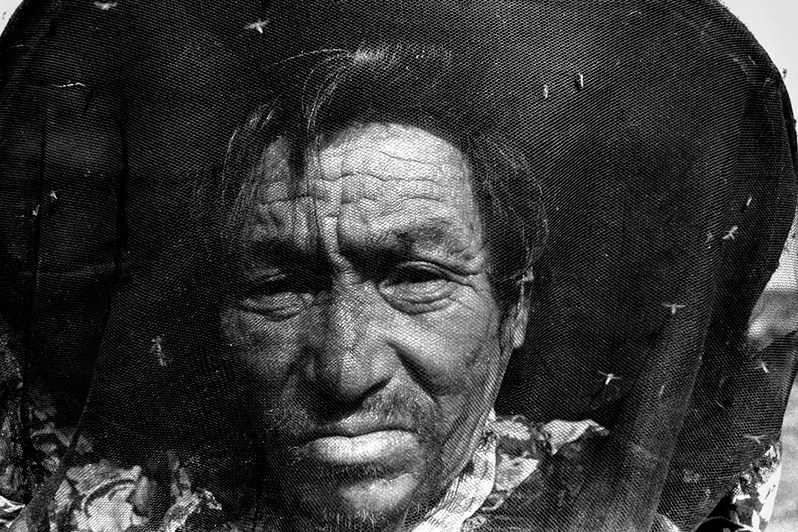

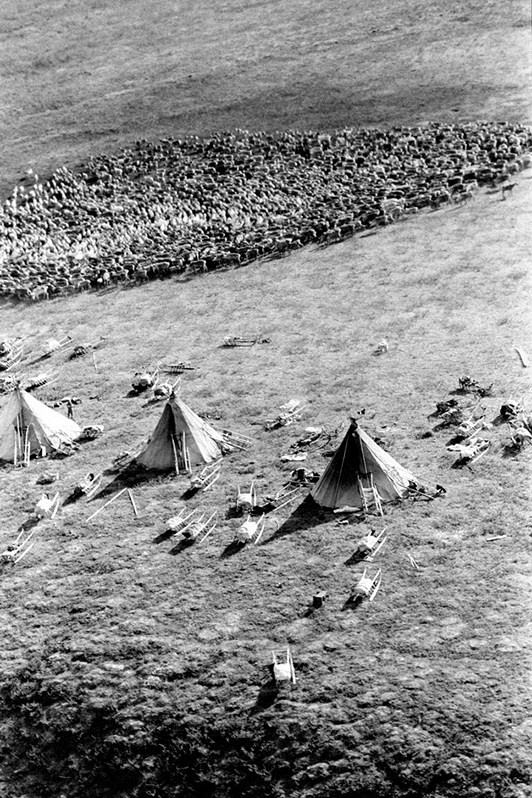

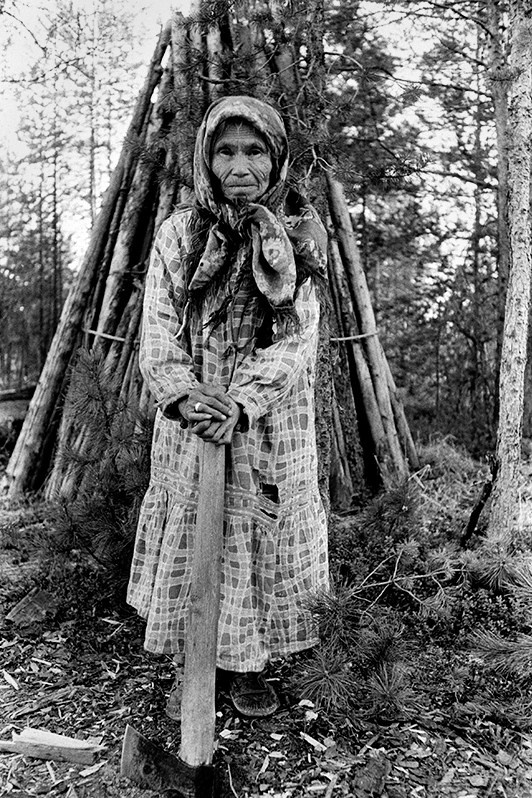

We landed near Brigade 1's car park, which was in a marshy area. It seemed that I found myself in another civilisation. People dressed in animal skins (malitsy) on one style of grey colour, island-topped plagues, dull tundra, and as for evil ‘there was a big mosquito’. The helicopter on which we arrived belonged to the sanitary aviation and made a special flight. Outwardly everything looked decent: the medics were dressed in white coats and behaved culturally, but the medical examination procedure was so fast that I did not have time to film it. In general, in Moscow doctors also do not treat patients with excessive attention and care, but here the process was going at record speed. People in white coats entered the tent, stepped over the dogs, asking on the way: ‘Will it bite?’, looked into the children's mouths, put packages of pills in the hands of women, politely greeted the men and went outside — that's it, this family had already joined the ‘free medical service’. Symbolically, ten days after this examination, an 11-year-old girl died in the brigade and was buried there in the tundra. I am not going to judge anyone, God forbid, the medics know the local conditions better, they have a hard job, they live there, after all, but I feel sorry for their patients.

Yes, I was already afraid of this man, the way an athlete is afraid of a fight when he has been told so many untruths about his opponent that it is time to give up. But there was nowhere to run. Towards evening I was already on board a huge barge, which by order of the local authorities was to be dragged in the old way, making a circle to bring me to the shaman. The barge, in addition to its cargo, had been adapted for habitation. There was a small cinema hall, a kitchen with a dining room, and a dozen four-bed cabins. It was pulled by a small tugboat on a cable.

I was too late to film, all the people had settled down, as happens on an evening train. The only thing left to do was to film eight heels or a lonely native coming from the loo. I was getting dreary. On the bow I tried to film deer barks, but they did not raise their muzzles neither to whistle nor to stomp because of the heat, and only lazily wagged their ears in my direction.

Behind the stern of the barge, shining in the sun, a string of fifteen boats tied up one after another in three rows. It wasn't for me; I was shooting people, not scenery, but the beauty of the caravan beckoned me to take a few shots. I mentally asked myself, or the shaman, who had so little film left, whether it was worth it. The answer came to my swollen head: do your own thing, shoot people, landscapes are not for you!

The heat was unbearable, but I still climbed onto empty petrol barrels and, as it later turned out, managed to take only four shots. I found that out when I developed the film. Suddenly, the cable of the tugboat pulling the barge broke. And it crashed at full speed into the precipitous shore. The impact threw me to the ledge of the second deck, and I barely had time to catch my arm, hitting my shoulder painfully. A little more and I could have broken my head and fallen into the water, unconscious, and then the swift waves of the Siberian river would have closed over me.

I am not the first time in the eye of death. In the Caucasus I had been strangled with the narrow leather strap of my camera, and it would not tear. But then I had no argument with the shaman. So, before I even met this mysterious man, I received my first warning.

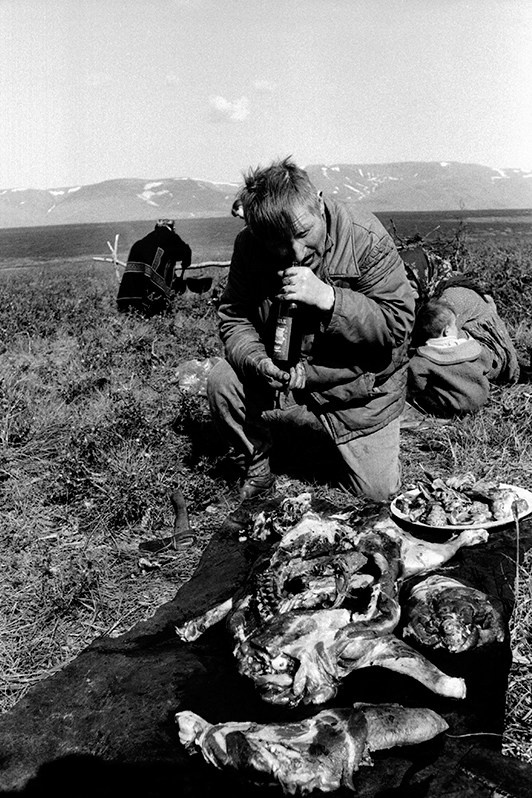

The captain also fuelled my interest in the shaman by telling me a funny story: ‘We are sitting by the fire with the shaman, cooking soup. One of us says: there is no bayberry. The shaman answers: the soup does not require it yet, the fire is small, it will burn a little and the bayberry will come. Suddenly we hear a motorboat scraping against the stream. We laugh, we say jokingly that it is a bayberry swimming. The shaman waves his hands and asks us to stop, but they don't say a word and keep on swimming. We went round a corner and suddenly we hear the engine stalled. And that's right — they had a bayberry.

It was four o'clock in the morning when the tugboat and the drunken captain amicably announced my arrival. The head of the fish farm, a Tazov resident, would not let me off the barge, explaining that he had instructions from above, and first we had to prepare the site for the photographer from Moscow.

— Sleep, correspondent, sleep,’ — with these words a troop of three men with three bottles jumped overboard. I sadly saw them off with my eyes. They would spoil everything for me: they would get the shaman drunk, what would I film? I waited until they had plunged almost waist-deep into the water, passed the shallows, came ashore and disappeared from sight, and returned to my cabin.

I was freezing. The North, among other things, had given me some kind of disease that gave me chills. In spite of the heat, the cabin was cool and the sheets were damp. I need not tell you how one sleeps on such sheets when one has chills. I'd rather tell you about a dream I had. I dreamt that some men were drowning me in a sack, that I resisted and realised that I was stronger than them and that nothing would happen to me.

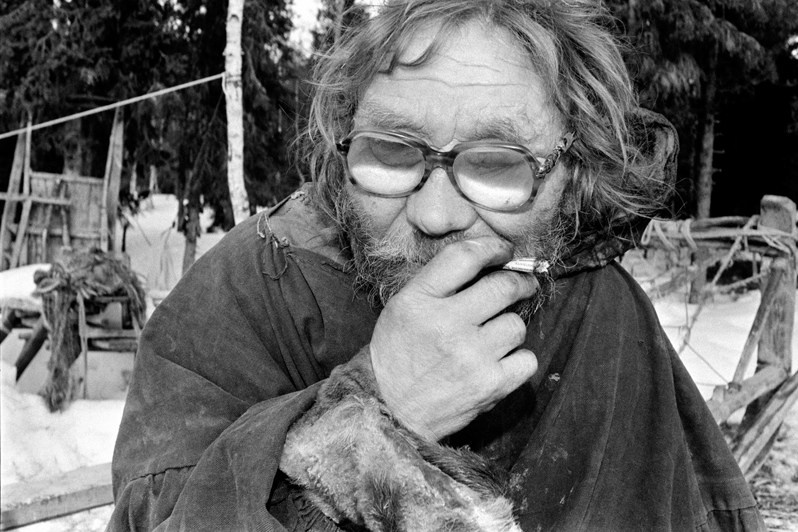

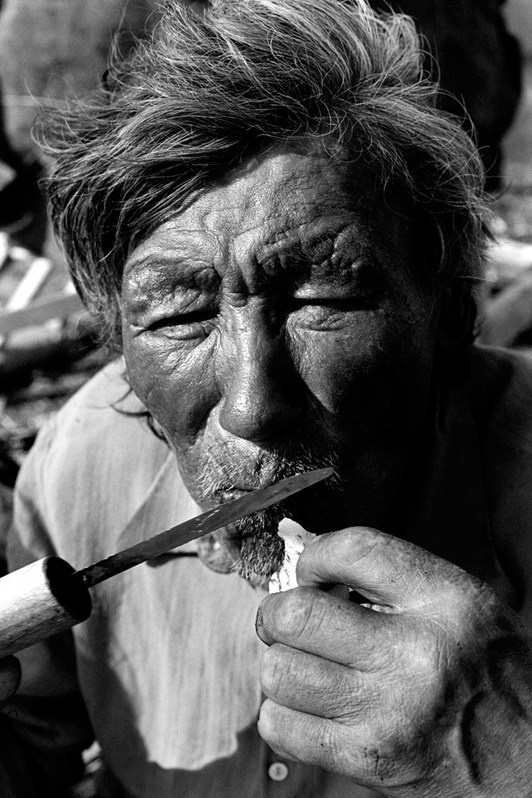

I clearly feel that I am suffocating, floundering, but I swim out, greedily grabbing air with my mouth.... and woke up, throwing off the blanket wet with sweat. What was my amazement when, just a few hours later, the shaman told me my dream. The shaman had a strange surname — Mandakov. His father inherited it from a Russian geologist, who found him in the tundra as a baby dying of hunger. He gave the foundling his surname. Grigory Mandakov sounds proud. I didn't notice anything proud in the shaman himself: the laundered waffle towel with which he tied his head made him look more like an old toothless baba. But I digress.

In the North it is customary that if a man falls into the water, he is not rescued, for there are ‘lower spirits’ — they will judge. So,’ said the shaman, ’after beating me, I was pushed into a new sack. It was firmly sewn from the sides, but there was a seam in the middle, which, by my luck, was not stitched all the way through. That's what saved me.’ When he swam out, his ‘well-wishers’ repeatedly confirmed to the tundra people that he was not from the tundra.

Listening to his story, I understood that having learnt from the ‘troopers’ about my arrival, the shaman, preparing for the meeting with me, had imagined in advance that he would tell me how the men wanted to drown him for the allegedly stolen deer, and I, in a dream, as if tuned to his wave, accepted this information.

To put it in modern terms: literally got into his ‘data bank’. And he wasn't a scary shaman at all. He was childishly boastful. He proudly showed me the metal snakes he wore on his chest when he cut himself with a knife. And under my arms,’ he said, ’I hide bags of deer blood.

I have presented, as it is circled by the plague in the blueskom kostra, and as pugazheny nentsy, when he shamanya, begins to strip itself by the bosom nostromom and blood. And as for the white birds that flew up from the chum, it is hypnosis and strong slaps on the back of the head, standing people around the fire. And why strange reindeer come to his plague, he explained; not far from his dugout there is a place where they like to lick the tundra (obviously, these are salt mountains). So it turned out to be much simpler than that.

The shaman lived in a dugout with his second wife, who was almost three times his age. Mandakov had neither served in the army nor worked for the glory of the North, but had spent his whole life in the field of occultism. The next morning he promised to take me to his museum, which he said everyone was delighted with. But it was far from the dugout....

I always suffer that my face gives away my thoughts. After long conversations, by morning he became uninteresting to me, and only the desire to shoot more made me play along with him, and the boat was to come for me only in the evening. The only thing left to do was to film the museum — the workplace, as the shaman himself said, but he suddenly became obstinate, sensing the change in my mood, and left to cut the fish.

It was only a few hours before departure. I started running like a rabbit from the fire to the dugout, then down to the river, and every time I saw the shaman at his sluggish work, I shouted:

— What about Moscow, and the money for the tickets, the country is suffocating, waiting for a report about the shaman, and you are here quietly cleaning fish.

I persuaded him for half an hour, to which he threw up his hands and replied: ‘Your bad man, you came and the sun ran away. Needless to say here that not only patience is torn, but also clouds. Before these lines I did not lie and now I swear by my health: the ray of the sun at first illuminated only our floodplain. The river and the bank opposite were in pre-threat darkness, but after a few minutes the sun illuminated them too.

— Sasya, you, however, are also a shaman,’ said my best friend Mandakov. Now I am ashamed to remember how we were going to this museum. I seemed to myself at that moment like a waiter who had been dropped off in the tundra by mistake instead of Paris. I suddenly became very sociable: I looked into the shaman's eyes, but I kept squinting at the sky, fearing that the sun would again hide behind a cloud and he would again decide that I was a bad person.

The museum was in the neighbouring bushes. Behind them was a clearing where the shaman's wife immediately built a small fire, and I helped him pull a wooden artillery shell box from three birch trees. The first thing he took out were figures cut out of tin cans. He explained that they were kochmonauts. The first figure he named Gagarin. The next names were consonant with the names of Politburo members. The names of the new democrats hadn't got here yet. Also in the box were the usual Christmas decorations. There was a shard of mirror, glass bottles, rusted candy boxes. And six-pointed stars that the shaman used to put over his eyes for some reason during the ritual.

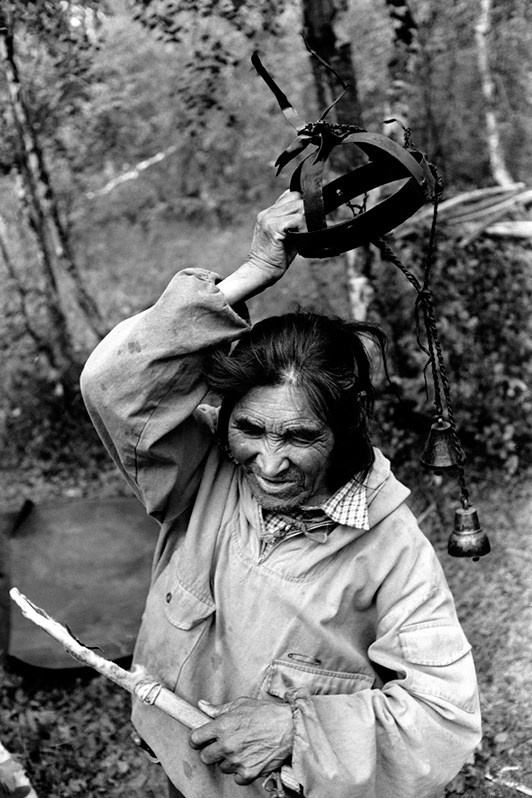

While posing for me, he was beating a huge tambourine and, raising his eyes to the sky, whispered something in the incomprehensible Selkup language to his spirits, shaking his shaman's trident. Through the slits of the eyes of a red fox skin, which was clad on the shaman's head, the blackness looked at me, and its tail moved in the wind as if it were alive.

In the excitement of the shooting, forgetting everything, I ran, jumped, fell to the ground with my knees, and by the end of the shooting I was so sweaty that the same heavy-breathing shaman suddenly took off the fox skin from my head and said: ‘Your hard work, take a present to your wife. The untanned pelt crunched quietly in his hands. My wife, of course, would not wear it, but I dared not refuse.

At home, I proudly displayed the trophy of my business trip. We hung it on the wall. But, when one day on the ‘box’ there was a conversation about biolocation, I made frames out of thick copper wire and walked around the flat with them. What was our surprise when, as we approached the skin, the frames unfolded with such force that they literally hit our shoulders.

For the sake of purity of the experiment, we blindfolded our visiting friend and moved him to another place. When we began to check, the frames did not turn at the place where the skin had been hanging before. But as soon as he approached the hide again, they turned round again. It was clear, without any doubt, that this was their reaction to the fox skin.

— Let's get rid of her,’ my wife said to me, frightened. I couldn't believe my ears. If that's what even my thrifty half thought. I took the skin off the wall and let it fly off the balcony.

We have a corner flat on the sixteenth floor. I saw her float through the air and fly sideways behind the house. Pushey tails its masses as a rudder. I laughed at the thought that she could be thrown through a window by the air current. When I imagined the frightened faces of the owners, I was amused.

I had already forgotten about the shaman's ill-fated gift when my wife began to complain that her feet were burning. I didn't pay much attention to it. They are the weaker sex. She complains, she wants me to feel sorry for her. At two in the morning I woke up to hear my wife talking to someone on the phone. She was again complaining that her feet were burning, as if she had been put in a bonfire.

— Isn't it cancer?’ she asked in a trembling voice. I quietly picked up the parallel receiver and heard the ambulance doctor answer irritably:

— Raka, shit. It's 2:00 in the morning, you're asking stupid questions. Take a bath and go to bed.

I dozed off to the quiet murmuring of the water. In the morning my wife was surprised to tell me that the burning was gone, and she ran to the pond for exercise as usual. She came back very quickly and told me the stunning news that she had seen a fox skin on the pond, which was lying in the extinguished fire with a burnt back part.

Alexander Shchemliaev 1993

SEVERIANE Magazine No. 1, 2014