To Dima Markov: in memory of the photographer

Irina Chmyreva

Life is a form of poetry and, as befits this musical art form, it is filled with rhymes and prosody. Repetitions of words and events may go unheard or unnoticed, but they point to an inner similarity that remains to be examined. To be understood.

Two people died in Russia on the same day. Usually, XXX people die in the country every day (I won’t check the statistics, look them up yourself if you want to marvel at the cosmic scale of the cycle of life and death in nature). But the passing of these two was perceived as catastrophic by many citizens. The death of citizen N marked the end of the fairy tale about the possibility of change in society. The death of photographer Dima Markov outlined a black hole in the place of possible documentary photography in a democratic society. That’s right: what he did was tell stories about how people live. Children. Invisible until famous actors play them in the next TV series, residents of the outskirts. More precisely, the outskirts are designated as a backdrop, and those who were born there and will die there have become the pale shadows of themselves on the glossy screen. It wasn’t like that for Dima. They were real. Sharp, crooked, like an old knife that hasn’t been sharpened in a long time, which cuts even more painfully, more deadly.

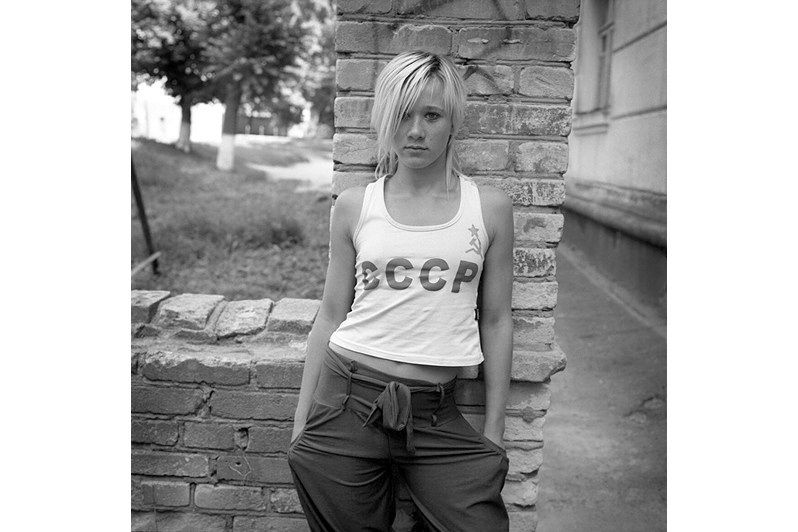

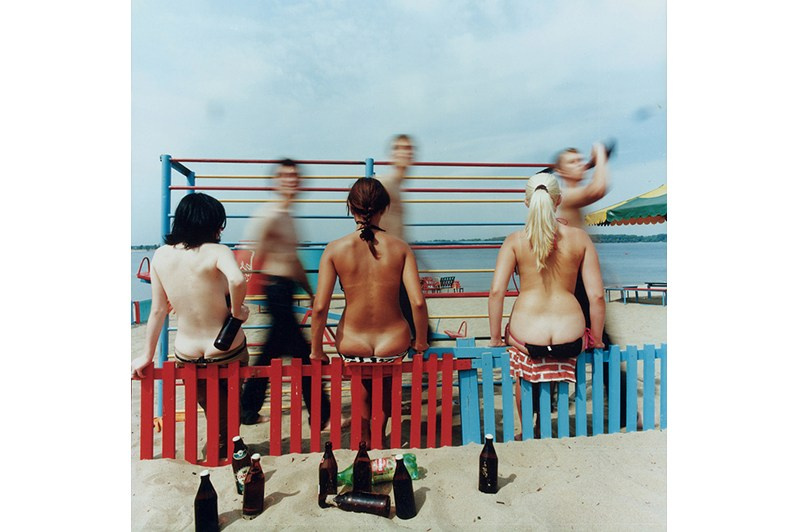

His characters were stirring. Hiding behind his colourful escapades, educated viewers could engage in discussions about the superiority of black-and-white photography over colour and the greater significance of the old documentary school compared to the Instagram generation (owned by Meta, recognised as extremist in Russia). But all these well-constructed conversations among clever intellectuals did not touch on the essence: the one that frightened and forced people to turn away and seek refuge behind the black and white and the veil of time separating the documentary photography of Shchekoldin, TRIVA, and Semina from our days. And life, growing with recognisable symbols of the present, cheap Chinese mobile phones in bright cases and garish T-shirts and crappy slippers, remained at its core the same, tearing the viewer of Dima’s photographs apart like a dangerous bullet from within.

The unpredictable effect of encountering a photograph from a first-person perspective. It seemed that such photography could be taught in schools of colourful, lively reporting, but the empathy and pain that a photographer experiences in the field cannot be taught. And so Markov was alone. The paradox is that Dima was an aesthete. What he photographed literally exploded his colourful, harmonious vision, but he could not look away from the Gorgon of our time. Because, no matter how redeeming it might have been, it wasn’t honest. He could have photographed beautiful landscapes, and among his enormous legacy there are some, with pink mists over a blue river early in the morning, when the pain, muffled by the night’s haze, receded for a short time. But there aren’t many such “postcard” views. Not because he didn’t see them, but because he didn’t allow himself to.

The photographs that Dima took were, by and large, unnecessary to his contemporaries. After all, who needs a mirror without a frame? And it is looked into by an untrained child who feels so bad that he wants decorations, even if they are cheap, but shiny, covering up the darkness that can be so frightening. Unfortunately, nurturing society in a state of eternal childhood, escaping from the picture of reality into the world of AI dreams has become our development scenario in recent decades — and Dima’s photography did not lead in this direction.

When Instagram’s photography segment (owned by Meta, a company recognised as extremist in Russia) appeared in Russia, as it did around the world, Dima became its first megastar. Now it’s not just a long time ago, it’s from another life. I remember the first publishing projects that attempted to explore what contemporary Russian photography looked like on this network. Thanks to Instagram (the old one), photographers became visible to international agencies and editors of all kinds of publications, both online and offline. In that field, Dima’s position was still unique: hundreds of thousands of followers and the same response to each new publication. At first, when there was nothing to compare this new way of interacting with the audience to, Markov’s published photos were compared with what had come before. There was a moment (months, years — a moment in the long term) when Dimin’s boys were compared to the photographs of Maksimishin and Shchekoldin, but Markov’s success with the audience in such a system of evaluation seemed incomprehensible and therefore accidental. What was indisputable was that Dimini’s success testified to the audience’s visual hunger for photographs of themselves, seen not through the filters of glamour, but with the clarity of a flash of recognition, akin to insight.

Dima became the headliner of contemporary Russian photography in the world. Whether the photographic community liked it or not. The heavy burden of success. For documentary filmmakers, his supernova explosion was a sweet fairy tale of consolation: what they had been doing for years and what had remained on the sidelines of the artificial stage of Russian photographic life turned out to be in demand and resonated with people. Yes, resonance — interaction with the viewer, a story about the present and a reaction to it by time itself — this is what documentary filmmakers craved and were afraid to ask for, weighed down by constant accusations of “pessimism,” that old women and disadvantaged teenagers had already been photographed thirty years ago, so how much more could there be? Where is the novelty? … But the elderly and children, not captured by festive staged photographers, continued to exist, some were born and grew like weeds, others, having lived without love, grew old and turned into the image of eternal poverty in old age.

I remember being in New York during Dima’s first exhibition. A fashion design brand hosted it in their space, and leading newspapers covered it. When my conversation partners learned that I was Russian and worked with photography, their first question was whether I had seen the exhibition and what I thought of it. They told me about the crazy energy, about the beauty of these photographs. And about pain. Their own pain. They shared their life experiences with me, because Dima’s photography showed the possibility of learning about the pain in our country, and in this way his photography united people, becoming a bridge that allowed them to talk not superficially about general topics, but about the real thing. The real thing. At that moment, I regretted that skilful Russian 'photography as fine art', the beautiful prints of our masters, did not elicit such a response at photography fairs or among collectors. But this was the truth of life: the classical beauty of Russian photographic modernism could not, by its very nature, work as a key and a knife that opened up other people’s souls.

We never met Dima Markov. I saw his photographs and books, and heard people talking about them almost constantly. For me, it was both painful and joyful to see the younger generation of photographers and, thanks to Dima’s success and work ethic, his integrity and openness, to see a chance that the documentary school of contemporary Russian photography would not disappear, would not dissolve into the polyphony of photographic responses to the demands of the times. Only from outside the world of photography could one assume that Markov’s way of shooting was posturing or pandering to the viewer. His sharpness in judgement, his carelessness in public spaces, his way of life were a continuation of his endless trust during shooting. They gave him no chance to survive in the shadows. It was as if he himself was illuminated by a barrage of flashes. How long could he endure it? One day, his jet-set life came to an end, leaving behind a dazzling trail of photographs of our time. The seat is vacant. Applicants, prepare to walk barefoot on broken glass. Go ahead.

Irina Chmyreva 2024

Dmitry Alexandrovich Markov (23 April 1982, Pushkino, Moscow region — 15 February 2024, Pskov) was a Russian photographer, journalist and volunteer.

He gained fame by creating documentary photographs of provincial Russia and publishing them on his Instagram account. Markov took most of his famous works with a smartphone camera.

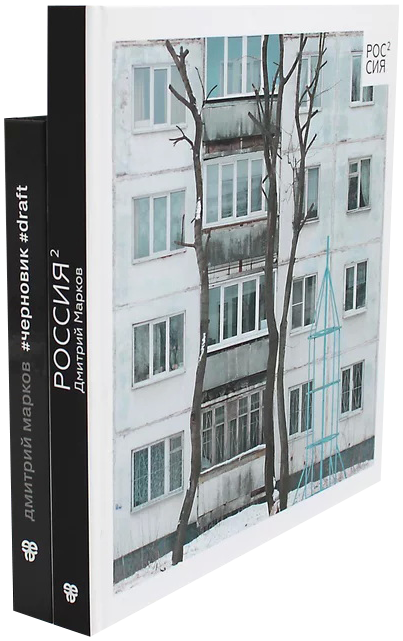

Dmitry Markov is the author of the photo books Chernovik (2017) and Rossiya v kvadrate (2021). The photographer’s works have been exhibited numerous times in Russia and abroad.

Markov has been volunteering since 2007, working with orphans from special needs children’s homes.