Up to the sky

Photographs by Ljalja Kuznetsova

Irina Chmyreva

The Boy with the Dove

Uralsk, Kazakh Soviet Republic, USSR. 1979

Her photograph with a pigeon and a boy has become symbolic. God knows who and what this definition refers to, but thousands of people around the world remember this photograph (as usual, without always thinking about who took it or what their name is), and those who see it for the first time fall in love with it. Perhaps this photograph is not only about time, not only about the personal, but also about photography in general. Remember: now the bird will fly away? Here it is flying, we see it, just as the boy who released it a second ago sees it, just as future generations will see it. We find ourselves outside of time, which remains fixed inside: here is the bird, here is the boy releasing it, somewhere in there, inside, and the photographer. The boy who released the bird is like the photographer, and the photographer is embodied in the boy. This young lad looks at the bird in surprise: what happened, how did it happen, it was in his hands. And now it lives its own life.

Uralsk, Kazakh Soviet Republic, USSR. 1979

One could recount countless times (and it has been done many times) how LK became a photographer. After burying her husband, with her little daughter in her arms, she began to take photographs, and this activity reminded her of her childhood, of the gypsies passing by, and she began to photograph their lives, their carts, their children. She became famous because her photographs were taken from within, and her appearance seemed to confirm once again that she was just like them, a vagabond, part of the boundless expanse, living with a sense of the vast sky. That part of the universe which, even though it repels, attracts. We are not always ready to admit to ourselves what civilisation means to us, just as the benefits of progress are by no means a measure of the value of life: we cherish them too much.

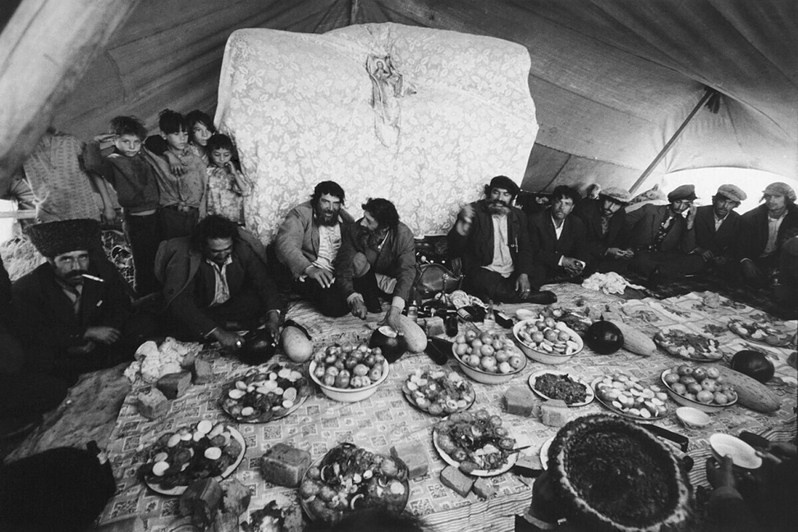

Uralsk, Kazakh Soviet Republic, USSR. 1990

Having spent decades photographing the Gypsies of the Volga, Kazakhstan, and Novorossiya (near Odessa) — the great steppes — Kuznetsova has in recent years been working on images of the Gypsies of Uzbekistan. They live there, becoming similar — for Europeans — to the surrounding peoples, while remaining strangers, newcomers, and dissimilar to the peoples of these lands. Too natural. If one can say “too” about living things. These people — the Gypsies — seem unaware that the camera immortalises. At first, they do not let it in for a long time, afraid like animals, but then they live alongside it, not at all embarrassed by their emotions, gestures, or physiology. Who do they let in? The photographer or the camera? It seems that they accept Kuznetsova in such a way that they allow the camera to be present.

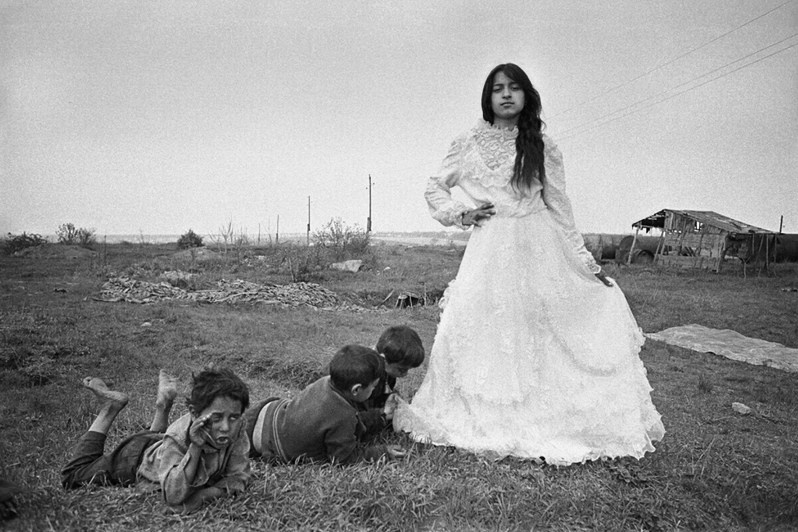

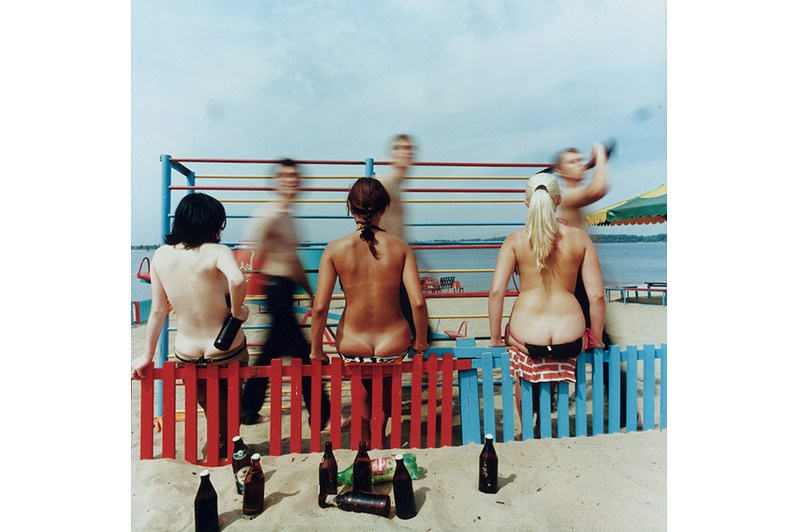

Odessa, Ukrainian Soviet Republic, USSR. 1990

She is ancient. As ancient as her Bulgarian ancestors were. She embodies an archaic feminine creative force, similar to that which drove the first women to depict totemic animals, men and women. Depicting a bride and groom, she can allow their heads to be cut off, leaving only their bodies; she can release a lone gypsy woman into a dance, leaving the grey signs of modern life behind the scenes. She is so impulsive in her photography that a child’s figure in a mask emerges from the shadows like a monster in a dream, rushing past the edges of the frame, past the viewer, happily separated from the plot by existence in another, colourful reality; she allows photography to be photography, an instrument, an impersonal viewer, that insatiable eye that plunges into existence, disregarding the laws of the accepted and the permitted. But the female photographer LK remains so much so that she spares and pities, does not hurt, but caresses with black and white shadows, enveloping the most dramatic characters in darkness, as children are wrapped in warm clothes.

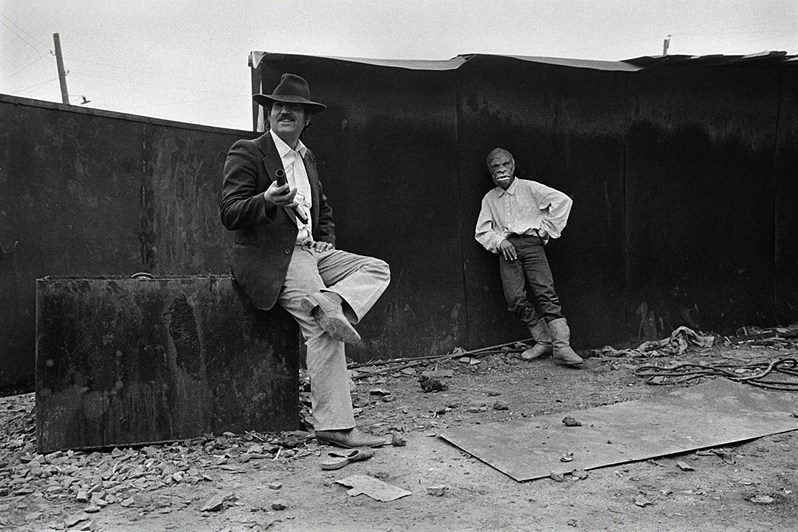

Odessa, Ukrainian Soviet Republic, USSR. 1991

For her, as for few others, in documentary photography, the tone of the print is incredibly important. It determines the depth of the dramatic intonation of the subject. The contrast of light and shadow, tied together in a knot like gypsy hair with dense grey tones, makes memories vibrate like the ringing of bells: the tone of the image affects like sound, like a primal sound, whose simplicity penetrates the archetypes of the subconscious.

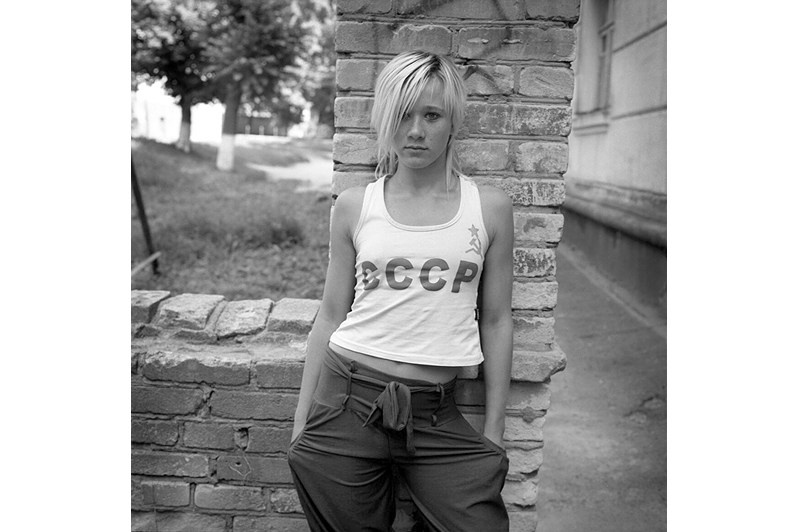

Usually, when talking about documentary photography, researchers refer to the characteristics of the author’s introduction, expressed in the uniqueness of the plot, the unusual composition, and the symbolic stylistics of the meaning. The author’s individual intonation reveals their special attitude towards the subject of the photograph. When talking about LK, it is equally important to mention the viewer’s experience in dialogue with the photograph. It is a simple catharsis that arises from the simplicity of the subject, the simplicity (primitiveness) of the composition, and the purity of form.

It is recognised and experienced as a personal acquaintance, an encounter with someone dear and close, honest to the point of bluntness and warm to the point of recognisable kinship.

Irina Chmyreva 2003