Sergey Chilikov

A photographer of one mission and a man with a thousand faces

Irina Chmyreva

Full version on photovisa.ru, June 2020

The news of the death of the photographer and philosopher Chilikov is a reminder of reality itself, the very reality that Chilikov had been fighting and transforming for nearly fifty years. This reality is the reality of the cosmic course of things beyond our control. The reality of chaos, Brownian motion, to comprehend order in which it is impossible, but we can recognise its absurdity. His destinies are incomprehensible, and His ways are unexplored. Sergey Chilikov managed to show the impossible — connections, intercontextuality of living life, to give the audience not a rational understanding of what is depicted, but heuristic admiration (as the ancient mystics knew it), when the meaning is given as a gift in the form of a single flash, is felt, but remains untranslatable into the language of words. In taking it in, the viewer also realises (extra-rationally) that words will distort and diminish the fullness of the coming understanding of the world. Perhaps it is the message of Chilikov’s death that is the sign that we are returning from self-isolation to a world that will never be the same again.

It is not customary for photographers to address first name and patronymic. But I want to address him as Sergey Gennadievich. The way his fellow philosophers and students knew him. Because the scale of Sergey Gennadievich’s contribution to our photography can only be described in terms of his main profession — it is the contribution of a ‘visualiser’ who changed the ontology of the photographic process.

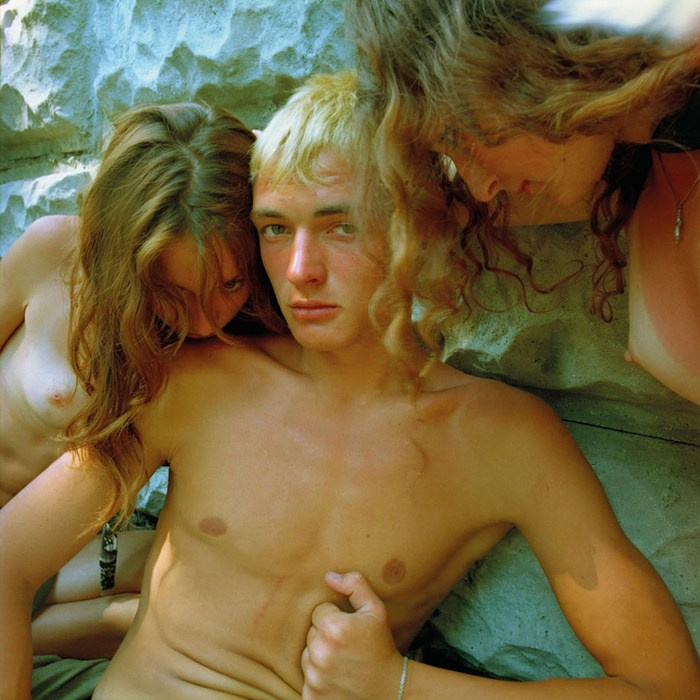

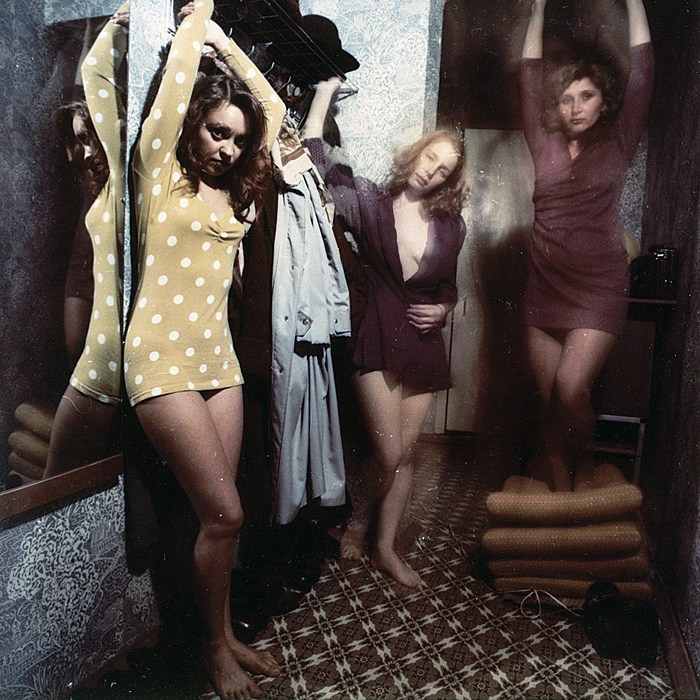

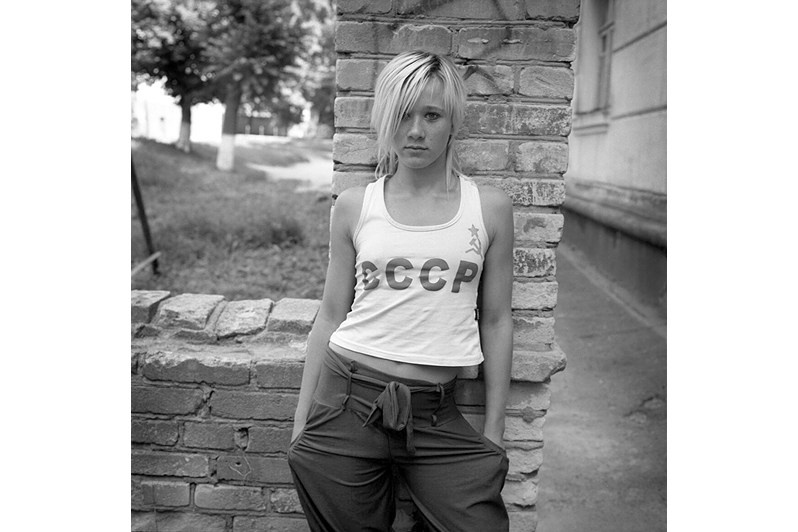

In philosophy, Sergey Gennadievich will remain with his book 'Artseg. The Owner of the Thing, or the Ontology of Subjectivity'. The book was published in 1993, when it could only have been printed, because the dependence of the problem of being — ontology — on the possession of an object and the creative variations of human activity arising in the process and as a result of possession (‘ownership’, according to Chilikov) was contrary to Marxist-Leninist philosophy, where the problematics of ontology were artificially made dependent on class theory. But the 1990s were a time when domestic intellectuals nearly drowned in an ocean of translated literature, and ties within the Russian philosophical milieu were so strained and thinned that Chilikov’s work did not receive the recognition it deserved. Sergey Gennadievich wrote a book. And continued teaching and photography. He spoke out. He presented an endured and formalised idea, and continued where people looking for literal connections between the philosopher’s occupation with photography and the photographer’s occupation with philosophy could not see them. His philosophical texts do not contain the words ‘photography’, ‘photographic’, he did not propose new theories of composition or vision, but his idea of ontology (being exclusively human, with inherent properties of the species sapiens) as the possession of things continued to be embodied in his own activity, which he, skilfully, philosophically playing with terms, called not photography, but visualisation. What is so delightful in his pictures — the Russian province, the manifestation of cultural archetypes in modern forms, the reaction (response) of his models to his provocations (skomoroshchestvo) and the involvement of the models in the game, replaying (even to the point of absurdity) the rituals of the everyday — all this can only be understood by understanding Chilikov’s method of mastering the world, subjugating it to his will.

Chilikov’s photography is possible insofar as he managed to transform and manifest the hidden essence of the reality with which he worked most intently. The shamanic barbaric freedom with which he tamed the world, subjugating it to his will and at the same time merging with its cosmic energy, because it is impossible to control it except by following this energy, appears to me in the image of Baron Klodt ‘conquering the horse’ from Anichkov Bridge in St Petersburg. Chilikov did not flirt with reality, but provoked it. Chilikov turned what was the nightmare of photographers of the documentary school: a man with a camera changes reality with his mere presence, causing, like a stone thrown into water, circles of backlash against himself, so that what he shot turns out to be a ‘spoilt’ or untrue recording of a living life — Chilikov turned it into a method that allows him to open up the outer calm layer of reality by provoking it with his presence, to invade it so deeply that the archetype hidden beneath ordinariness reveals itself.

Nothing like Chilikov’s ‘staged photographs’ (as many critics called them) had ever been done in Russian photography before him. But it is also impossible to repeat Chilikov’s method, since we are not talking about a crude intrusion, but about the surgical precision of Chilikov’s individual, skomoroshchestvo gift. One can try to copy the form. And, alas, we see in contemporary photography many examples of sloppily staged photographs, whose authors are perplexed as to why their work is not accepted by the photographic community. But imitating form does not mean understanding meaning.

In addition to the gift of disturbing space, pulling those threads that have broken out of the smooth and coherent fabric of reality and lead, like Ariadne’s thread, to the very essence of existence, Chilikov had excellent taste. He was distinguished by his understanding of the integrity of the image of a photograph and its author. Sergey Gennadievich’s theatrical skill and organics did not allow to doubt the image he created of Sergey Chilikov, as he appeared in the process of shooting, in his journeys from Yoshkar-Ola to Moscow, during his paid trips to Europe during his glory years for the presentation of the photo. He, a clever intellectual, played the role of a Russian bear, watching the honoured audience from the sidelines. From under his mask of a drunken man, he kept an eye on the cognitive dissonance of the recipients, controlling their attention at the moment of their confusion. Sergei Gennadievich Chilikov was a man who was bored. He knew what Boris Grebenshchikov calls ‘Old Russian longing’, which at other times takes the form of spleen, nostalgia and melancholy. People like Chilikov, such as Vasily Vereshchagin, were suffocating in the cramped framework of the art that was contemporary to them. Vereshchagin found a way out by participating in wars and secret operations. Chilikov — by turning to ancient practices of transcending the limits of the self.

Sergey Gennadievich appeared in different images for different people. With his peers he spoke seriously and respectfully, without hiding the richness of his language and the brilliance of his thought, while others were eupatised by his rudeness, playing the card of a ‘man of the soil’. In the circle of his close colleagues he will be remembered as an intellectual-people’s libertine, an educated smart man who ‘went to the people’. For those who looked at photography through narrow blinders, no matter whether they were made from the first-page images of Soviet journalism or from reproductions of foreign photography magazines, Chilikov was an incomprehensible and dangerous weirdo who could shave off the foam of random unstructured scraps of semi-knowledge with a single phrase. At the same time Sergei Gennadievich treated Sergei Aleksandrovich Morozov with respect and reverence, and, after his departure, those who came after him to study the theory and history of photography… I remember how a man from the photographic circle addressed Sergei Gennadievich as ‘Chilikos’. Realising that I could interfere and spoil his amusement, like a cat and mouse, with a shallow, narcissistic ‘representative of reality’ who was not worth a little finger of the great photographer’s knowledge or merit, Chilikov looked me sternly in the eye, without leaving the image of a drunken joker… I don’t know whether he was bored among those who took to discussing his photography, using the names of Western authors from the latest world museum exhibitions. I don’t know if he felt the bitterness of misunderstanding. I don’t know whether he was aware of the pride of the creator and the consciousness of his own magnitude.

What I know for sure about him is his crazy productivity in photography. In his archive, even scanned, the image numbers consisted of five digits. His image of a bearded man with a rucksack full of crumpled ‘cards’ did not fit with (and was not advertised by him) his careful and memorable treatment of all the selected negatives. He created the reality of his archive, so numerous and cosmic in scale that at some point he still lost power over it, something was lost, something remained in one print, which was not originally a photograph for him, but a card printed for purposes incomprehensible to photographers of his generation: by printing the outraged chaos, Chilikov returned it to the world, closing the circle of existence. This was not a photographic act, or even a narrowly performative one (to make the card part of the performance ‘photographer Chilikov’s appearance to the honoured public’), but a gesture on an ontological scale.

At the end of the seventies, Chilikov and his comrades experimented (in Soviet photography!) with collective shooting, when a performance begins to broadcast itself from within, since all its participants are photographers who act as models and observers at the same time. At the end of the seventies, Chilikov and his comrades began to talk and discuss photography, and from positions different from those adopted by the most progressive circle of colleagues from the ‘Lithuanian school’ of those years. Chilikov and his comrades created the Analytical Biennale of Photography, the first experience in our country of a conscious demonstration of photography within the professional community. Chilikov was a mediator of discussions; he not only generated new meanings, but created a field in which the talents of his colleagues' thinking were manifested. That is why, without in any way diminishing the merits of all the participants of the FACT group, I emphasise the exceptional role of the philosopher Sergey Chilikov. Although his fame and influence in photographic circles began long before the Internet era, it was his role as a mediator, a Mercury connecting different geographical centres, moving between them with a backpack of cards, that made him, standing in plain sight, a covert agent of the new photography. A photography he was creating himself. And propagandised it himself. But in a form that did not resemble official agitation, which everyone would recoil from. The propaganda of the new took a paradoxical form. He was laughed at like a jester, and then his ideas were repeated in an incredible way, confident of their originality…

Irina Chmyreva 2020

Sergey Gennadyevich Chilikov (1953-2020). Born in the village of Kilemary (Mari ASSR).

Graduated from Mari Pedagogical Institute. Candidate of Philosophy.

Participant and organiser in the creative photo-group ‘FACT’ (Yoshkar-Ola — Cheboksary) in the period 1976-1990.

Organiser of ‘Analytical exhibitions of photography (biennale) in Yoshkar-Ola’ in 1980-1989 and annual photographic plein airs ‘On Kundysh’ since 1980.

Publisher of the book ‘Photography in Yoshkar-Ola’ 1985.

Author of the book on Russian analytical philosophy: ‘ARTSEG. The Owner of the Thing, or the Ontology of Subjectivity. (Theoretical and historical sketch)‘ (Yoshkar-Ola, 1993).

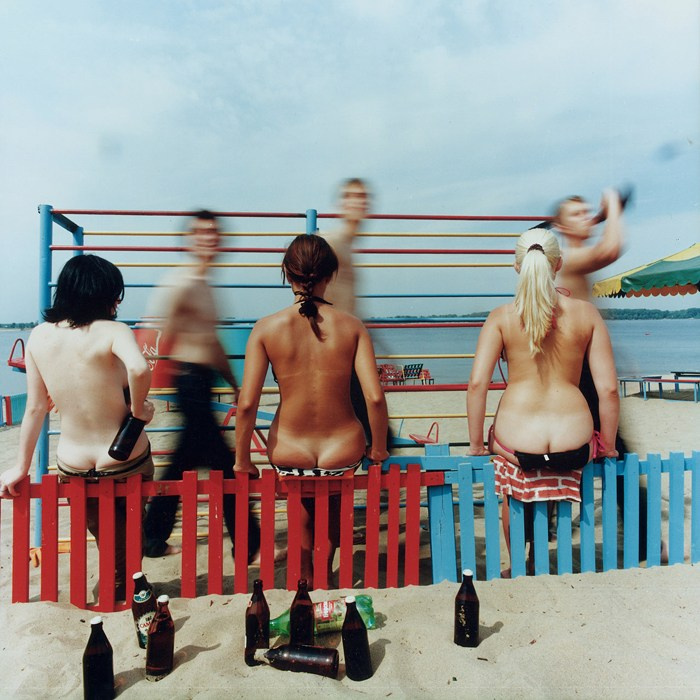

Participated with series of photo-works ’Photoprovocations‘, ’Village Glamour‘, ’Beach‘, ’Gambling‘, ’Philosophy of Travel‘ and others in festivals ’Fashion and Style in Photography‘ in Moscow, ‘Photobiennale’ in Moscow and ’Photographic Meetings‘ in Arles, France (2002) and others.

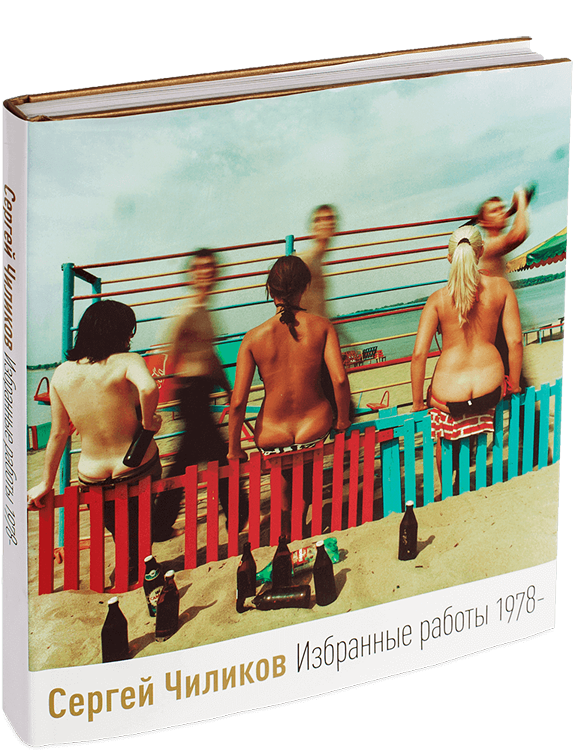

Sergey Chilikov Selected Works 1978-