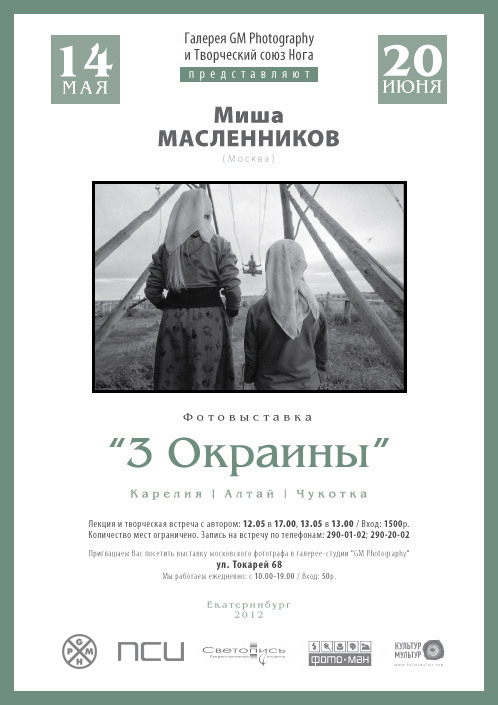

14 May — 20 June, 2012

Noga Creative Union and GM Photo Gallery present a personal exhibition of documentary photographer Misha Maslennikov, within the framework of which creative meetings with the author will take place. The exhibition project combines photographs taken by the author during the period of solo expeditions from 2005 to 2009 in remote corners of Russia: communities, settlements, villages of Karelia, Altai and Chukotka.

68 Tokarey Str., Ekaterinburg, Russia.

3 Outskirts: Karelia, Altai, Chukotka

Ethnographic interest in the way of life and traditions of the population of the Russian provinces is inextricably linked with the author’s philosophical quest and the joy of discovering something so familiar, but at the same time infinitely distant and forgotten by the inhabitants of big cities. The photographs, deep, imbued with silence and tranquillity, thus become not just a historical chronicle in its visualised provincial flow, but a significant psychological study aimed at exploring the traditional way of life, taking place against the background of radical changes and rearrangement of the new world order in a postmodern format.

For the author, travelling to remote corners of Russia is a kind of a trip for a “miracle”, which lies in the natural and correct course of life, unhurried, seemingly simple and ordinary, but meaningful and harmonious. And the photographic process itself, inseparable for the author from his spiritual quest, is akin to a miracle. The artistic reality of a photograph is born at the moment of “growing into” the plot and the author’s deep experience of the inner drama of the events taking place.

The “outskirts” in the photographer’s work are not associated with a certain geographical end or inhabited limit, but, on the contrary, are a transitional link to a more meaningful and holistic existence on the modern periphery. In exploring the way of life, customs and manners of the inhabitants of the “outskirts”, the author does not seek to capture rural “exotica”, shocking pictures of decay and decomposition.

The photographer deliberately avoids depicting the “diseases” of the province: drunkenness, poverty, thievery, etc. The life of “outskirts” in the author’s works is natural and unhurried, untouched by the corrosive influence of big cities. Hence the directness and childlike trustfulness of the heroes of the pictures, contrasted with common perceptions of the inferiority, limitations and savagery of the villagers.

However, this departure is not at all marked by a desire for pastoral idealisation of provincial life. The author does not close his eyes to the everyday life of the Russian provinces, filled with a lot of hardships and deprivations. However, another, wiser and more meaningful side occupies Maslennikov. The joy of overcoming difficulties, happiness, not tied to the acquisition of material wealth, the ability to rejoice in each day and to put up with failures become in the work of the photographer a defining step in the search for a way out and a cure for modern society in harmony, wisdom and beauty of the surrounding reality. Like the great Russian writer Dostoevsky, Maslennikov “…does not want and cannot believe that evil is a normal state…of man…” and sees the deliverance from the troubles and imperfections of society in fixing “positively beautiful” people. Social affiliation and often dysfunctional surroundings become insignificant before the beauty, inner integrity and harmony that are meant to save the world, despite the external difficulties of life in the Russian “outskirts”.

Anna Kolyadenko 2012

events

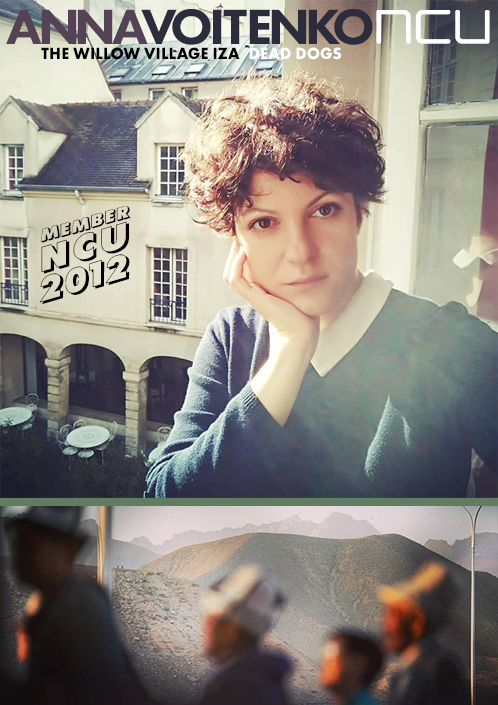

Anna Voitenko

Alex Melia

Eric Gourlan

Emil Gataullin

Moscow 2008

Alexander Shumskikh

Misha Maslennikov

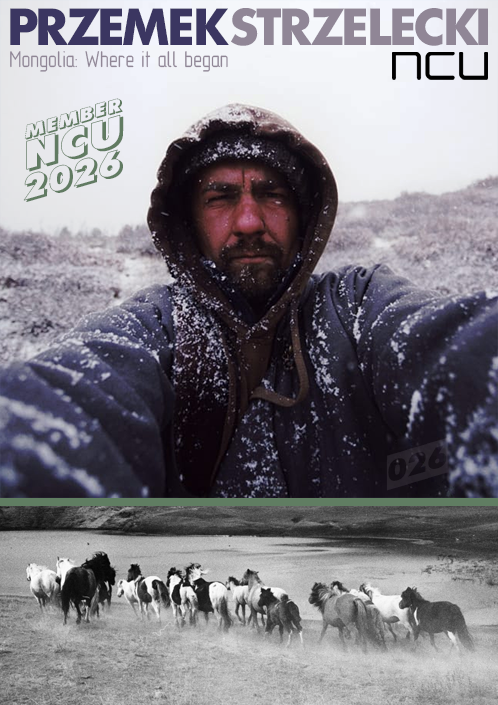

Przemek Strzelecki

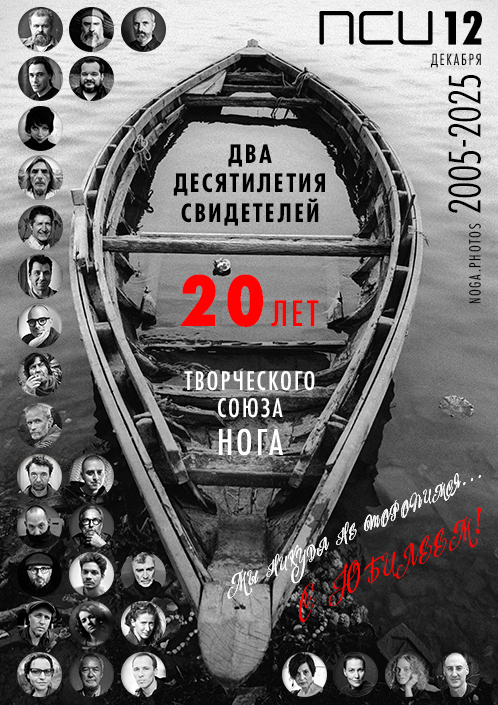

20 years of NCU

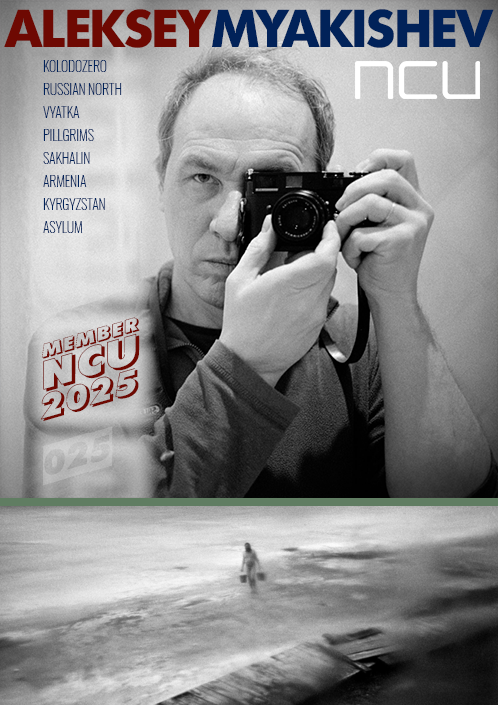

Aleksey Myakishev

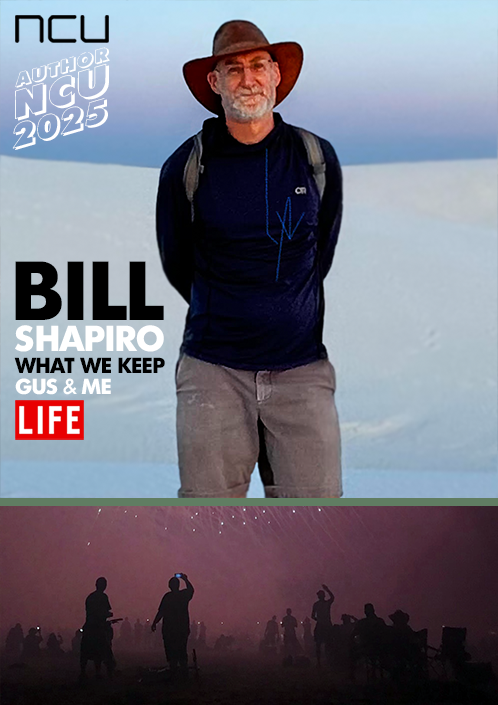

Bill Shapiro

Carola Allemandi

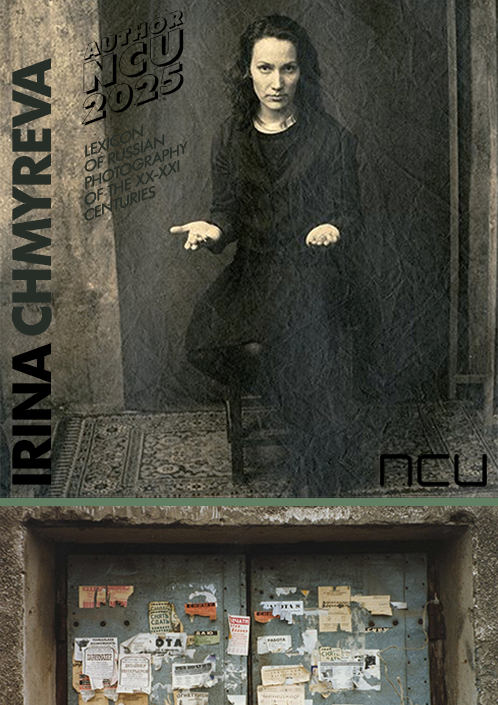

Irina Chmyreva

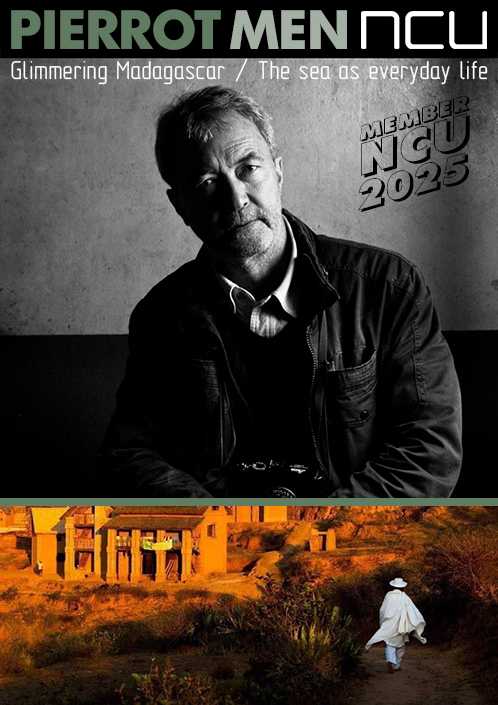

Pierrot Men